in Reins

/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\/\

scroll down below

founder's way of thinking

basics of network effects

sketching a business plan

pitches of successful startups

interesting resources

Readings

- Startup Playbook

- Paul Graham’s Essays

- Marc Andreessen's Blog Archive

- VC: An American History

- A History of Silicon Valley

- Donald T. Valentine, early Bay Area venture capitalists

- How Venture Capital Works

- The Power Law of Venture Capital

- How To Tell If You’re Winning Or Losing (The Secret Service Can Give You A Hint)

- Do Funders Care More About Your Team, Your Idea, or Your Passion?

- Forecasting & Scenario Planning

- Founders Tribune

- Startup Archive

- Wallstreetprep

Videos

individual

- The Venture Mindset

- Embracing Failure

- Doug Leone: Luck & Taking Risks

- Don Valentine: Target Big Markets

- Peter Thiel: Zero to One

- Ben Horowitz: Nailing the Hard Things

- John Doerr: Ideas are easy, execution is everything

- VC Decision Analysis

- How Venture Capitalists Make Decisions

- Wharton Business Plan

- Pitching Errors

- Beyond the Pitch Deck

- Harvard MBA lessons

- All you need to know about VC

series

Books

- Zero to One by Peter Thiel

- The Venture Mindset by Ilya Strebulaev, Alex Dang

- Venture Deals by Brad Feld, Jason Mendelson

- Secrets of Sand Hill Road by Scott Kupor

- Power Law by Sebastian Mallaby

- The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

- VC: An American History by Tom Nicholas

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things by Ben Horowitz

Pitches of Successful Startups

Here is some inspiration for pitch decks. Keep in mind that these are old..

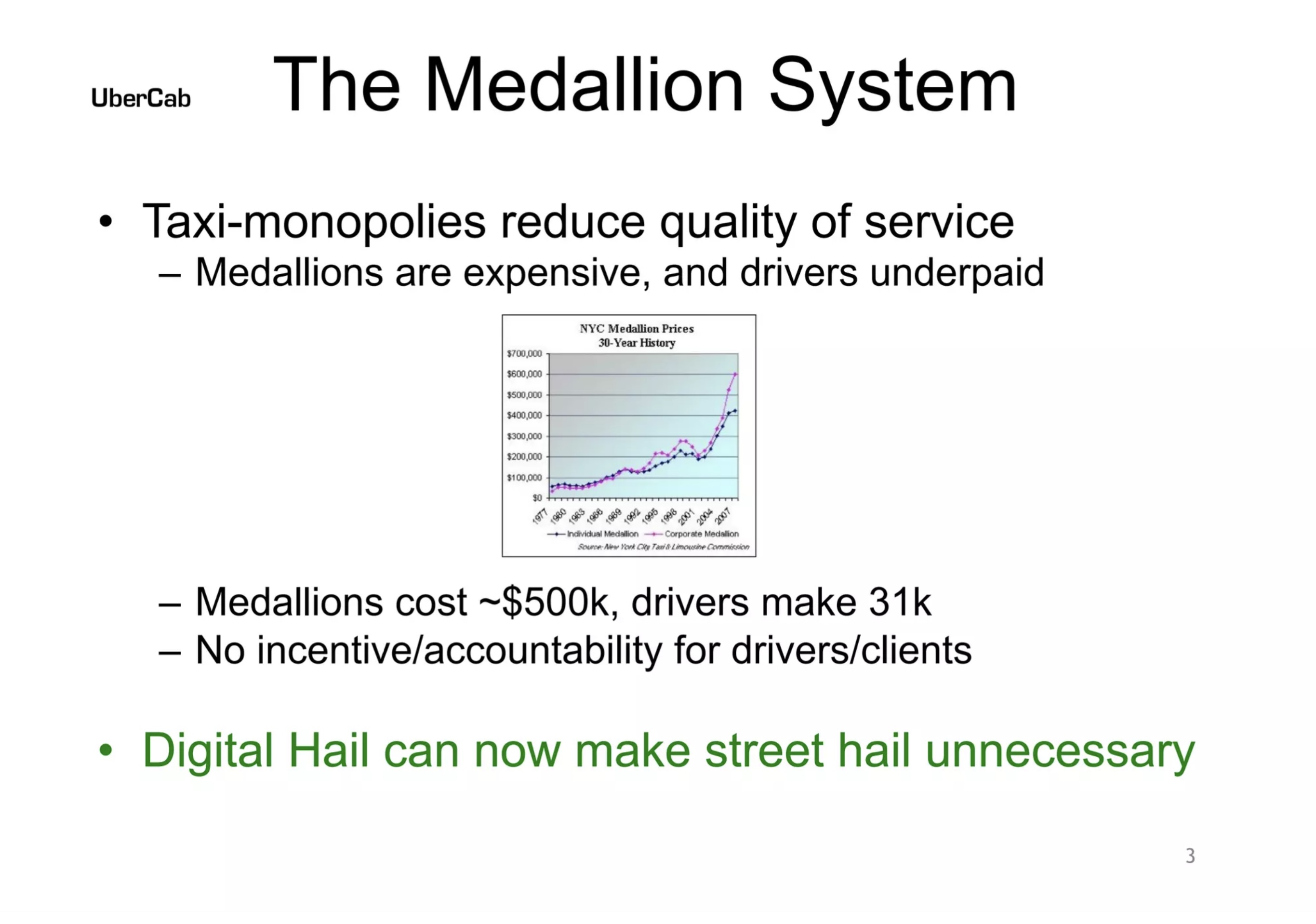

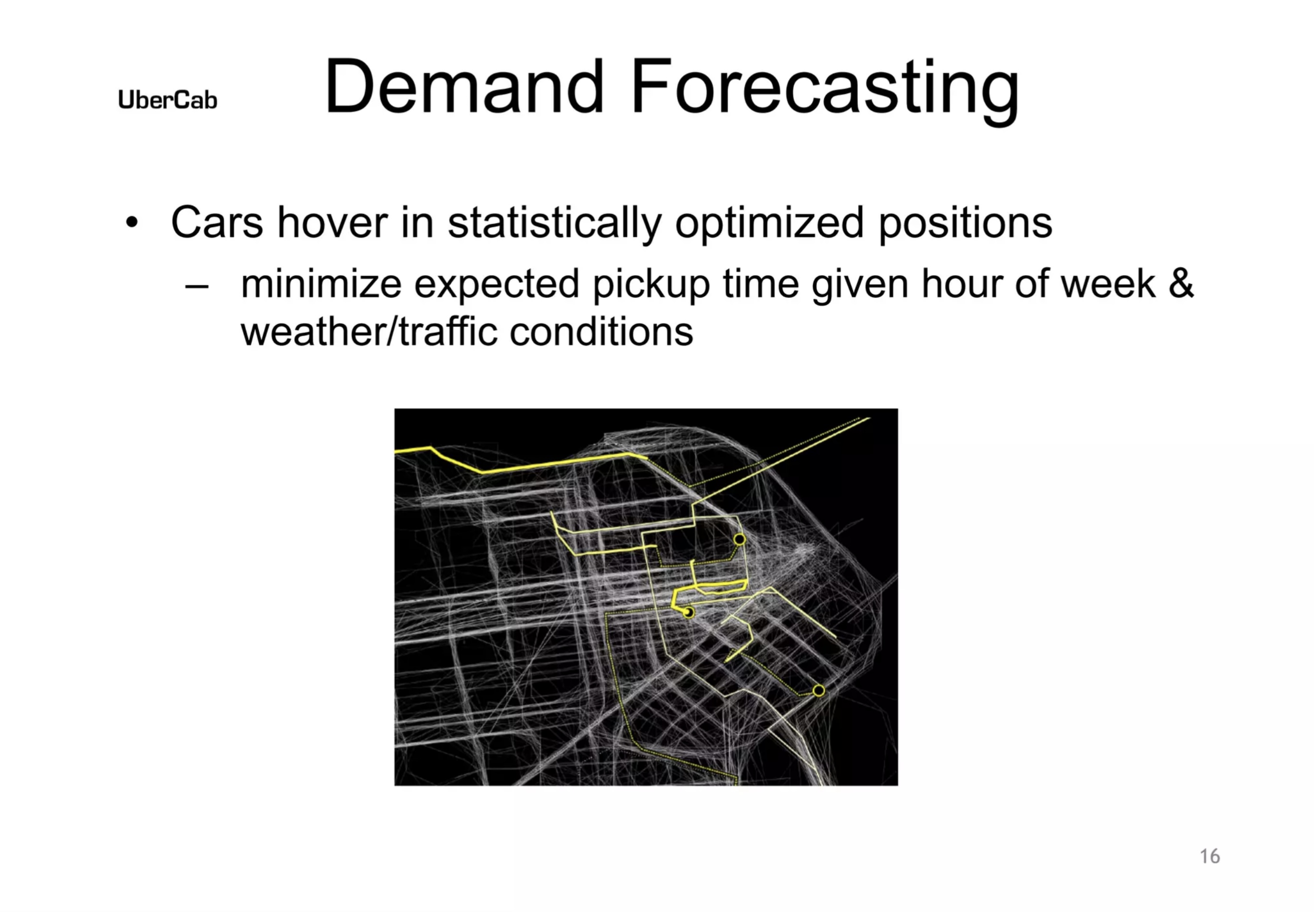

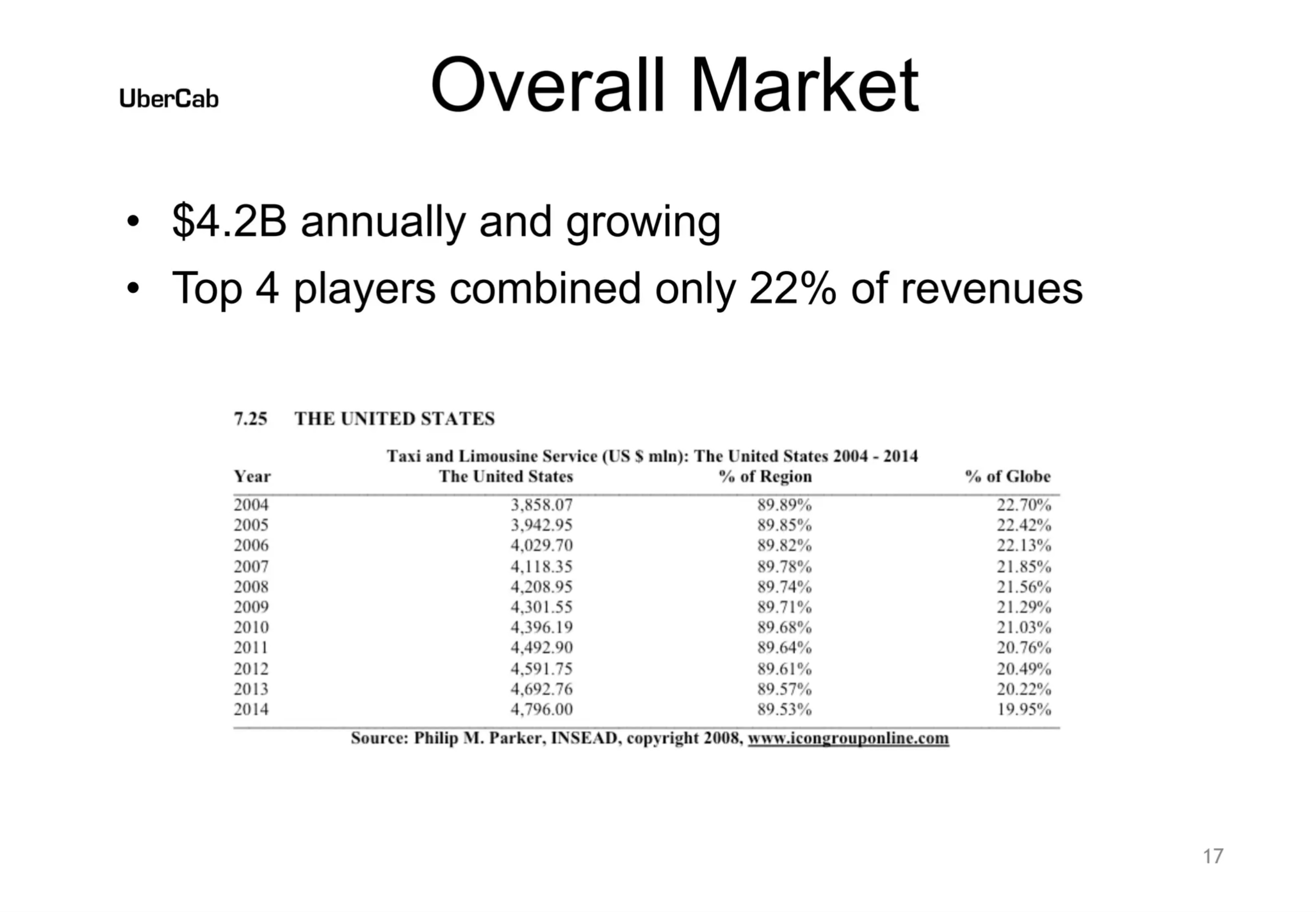

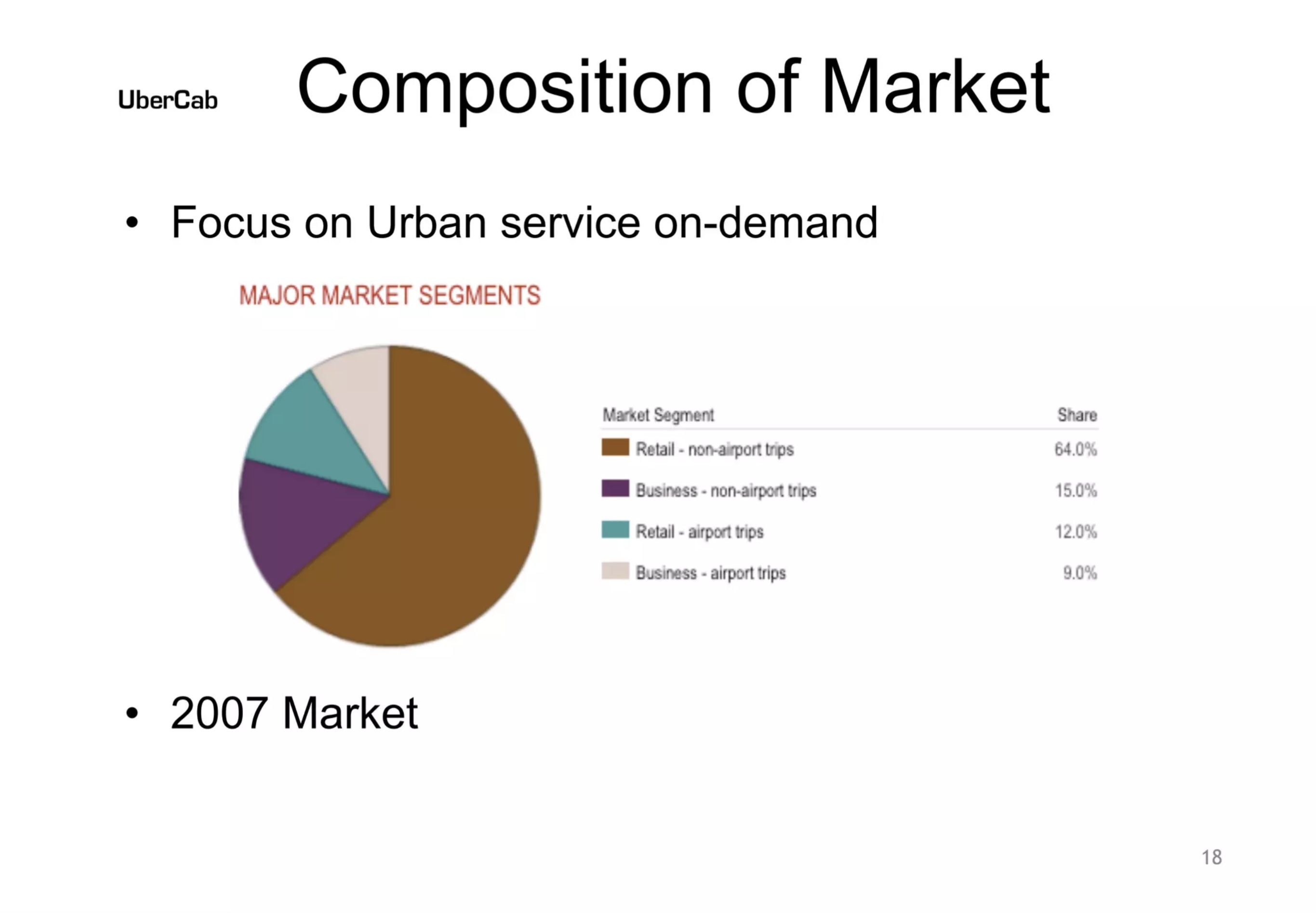

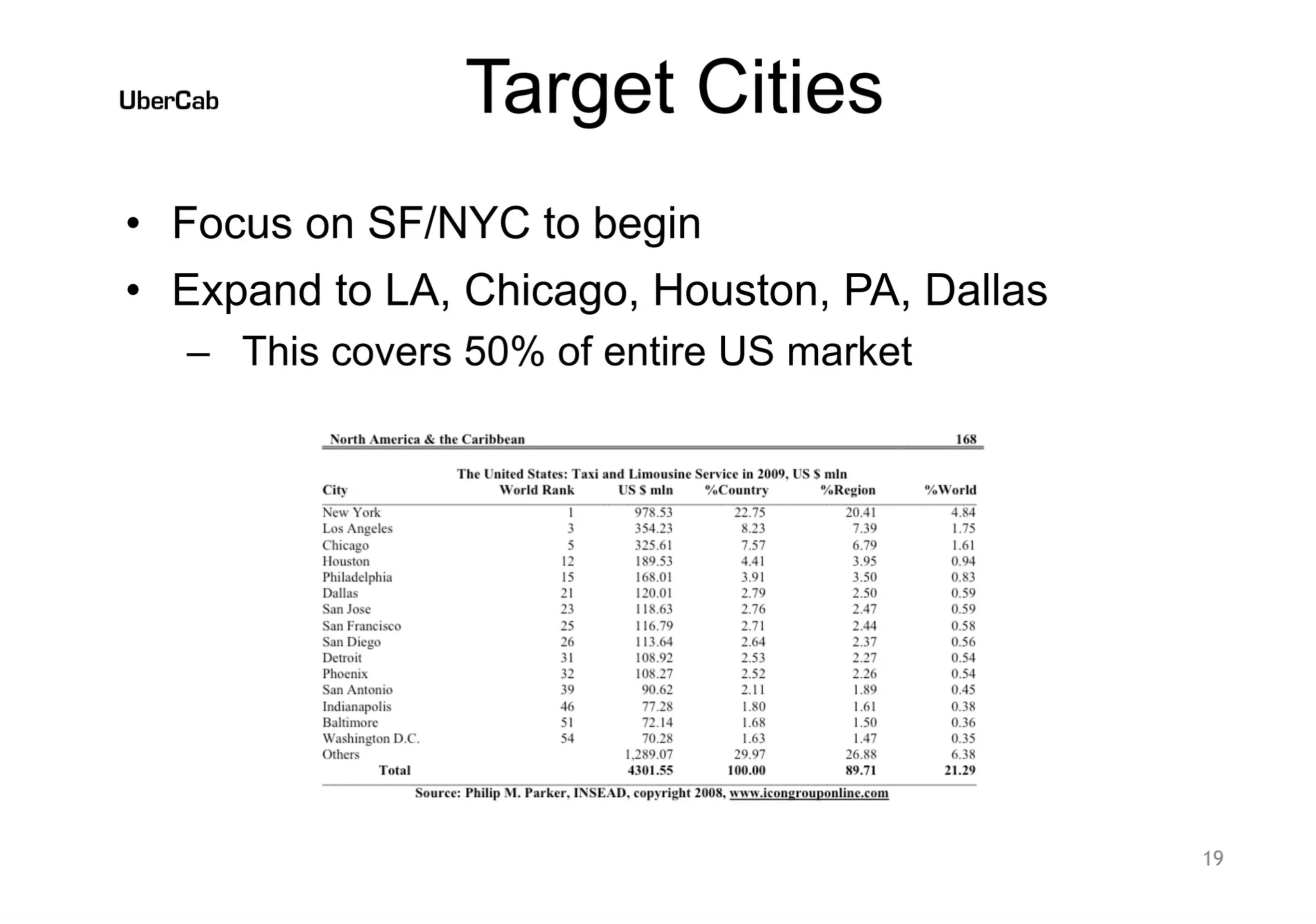

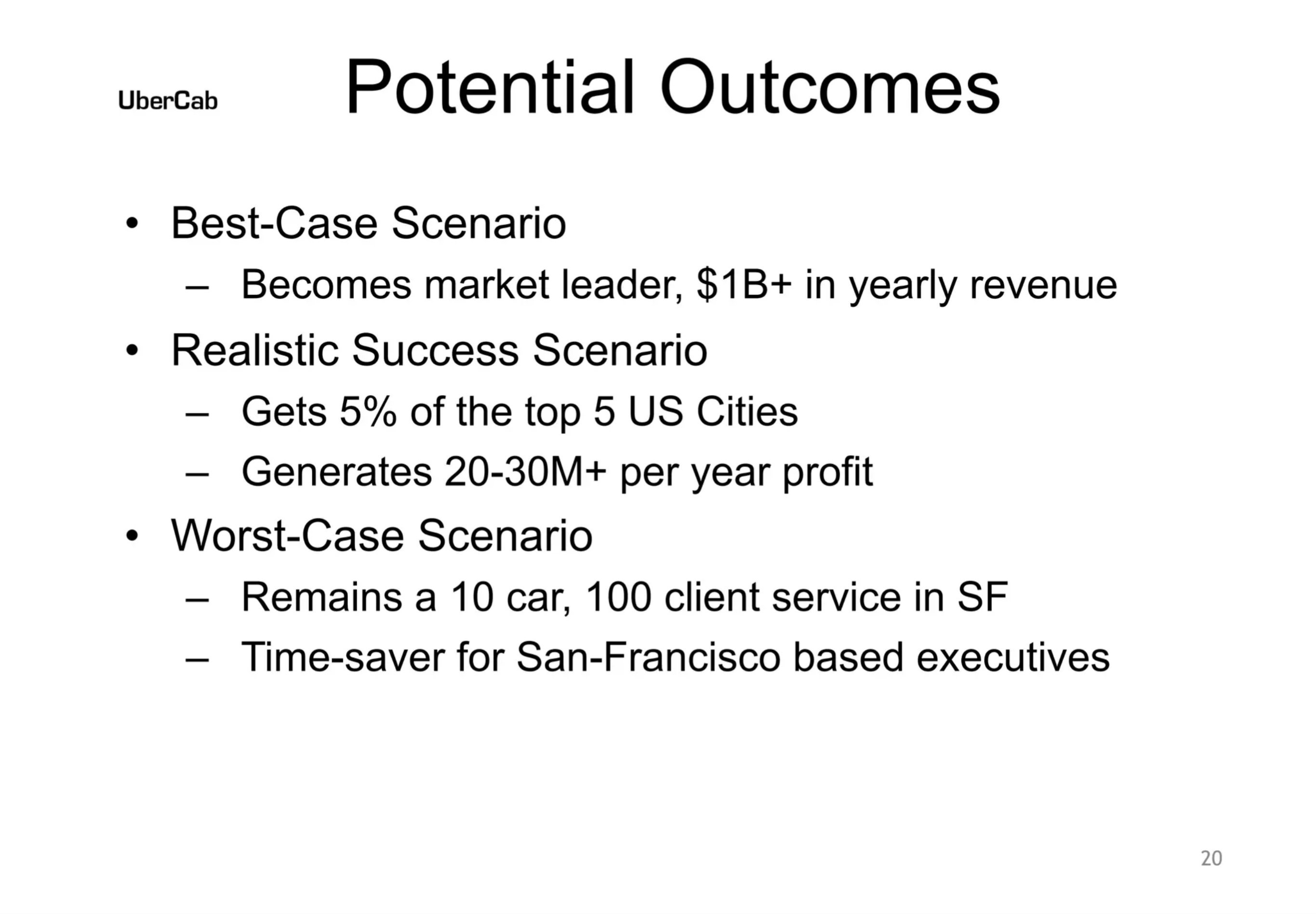

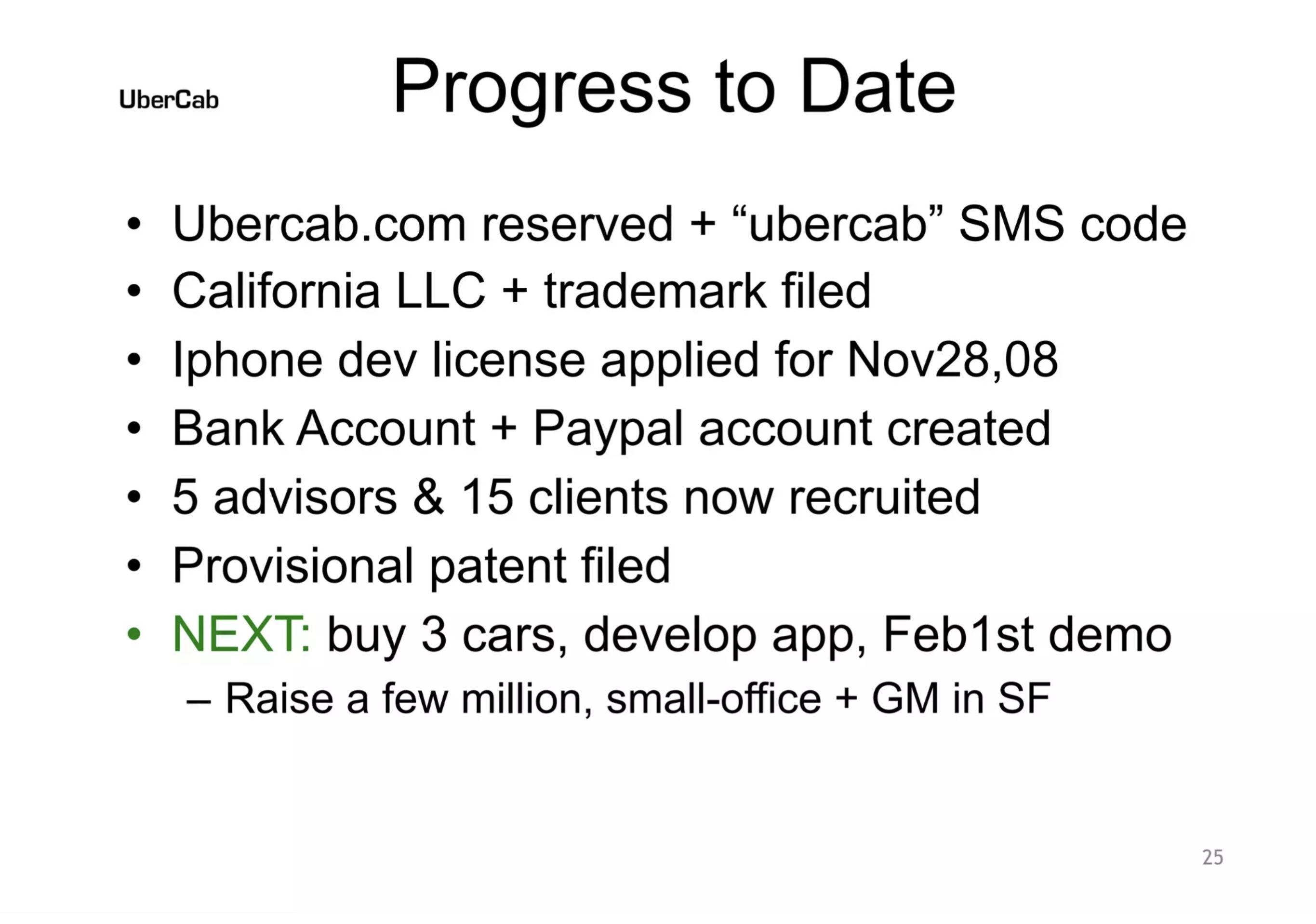

Uber

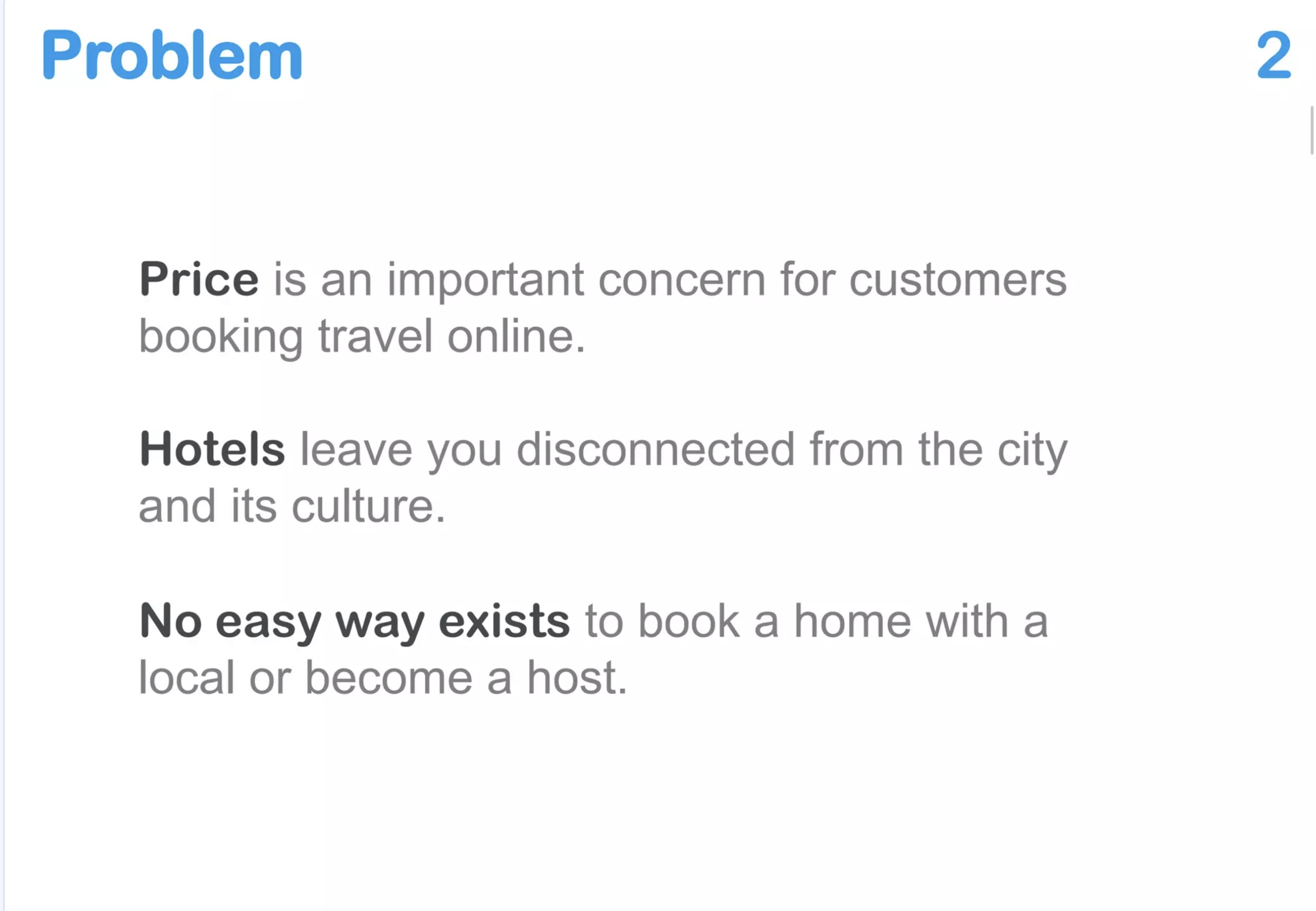

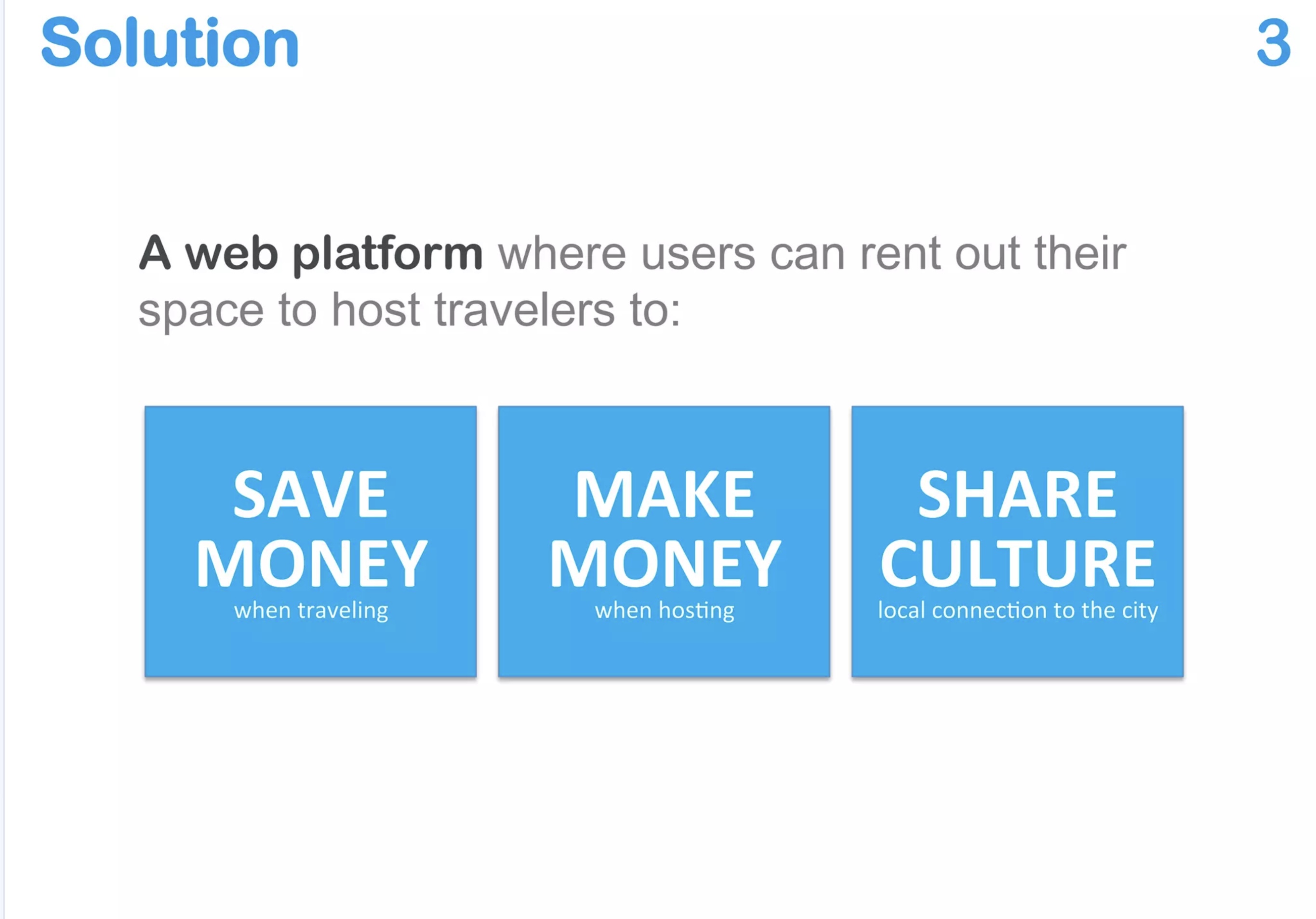

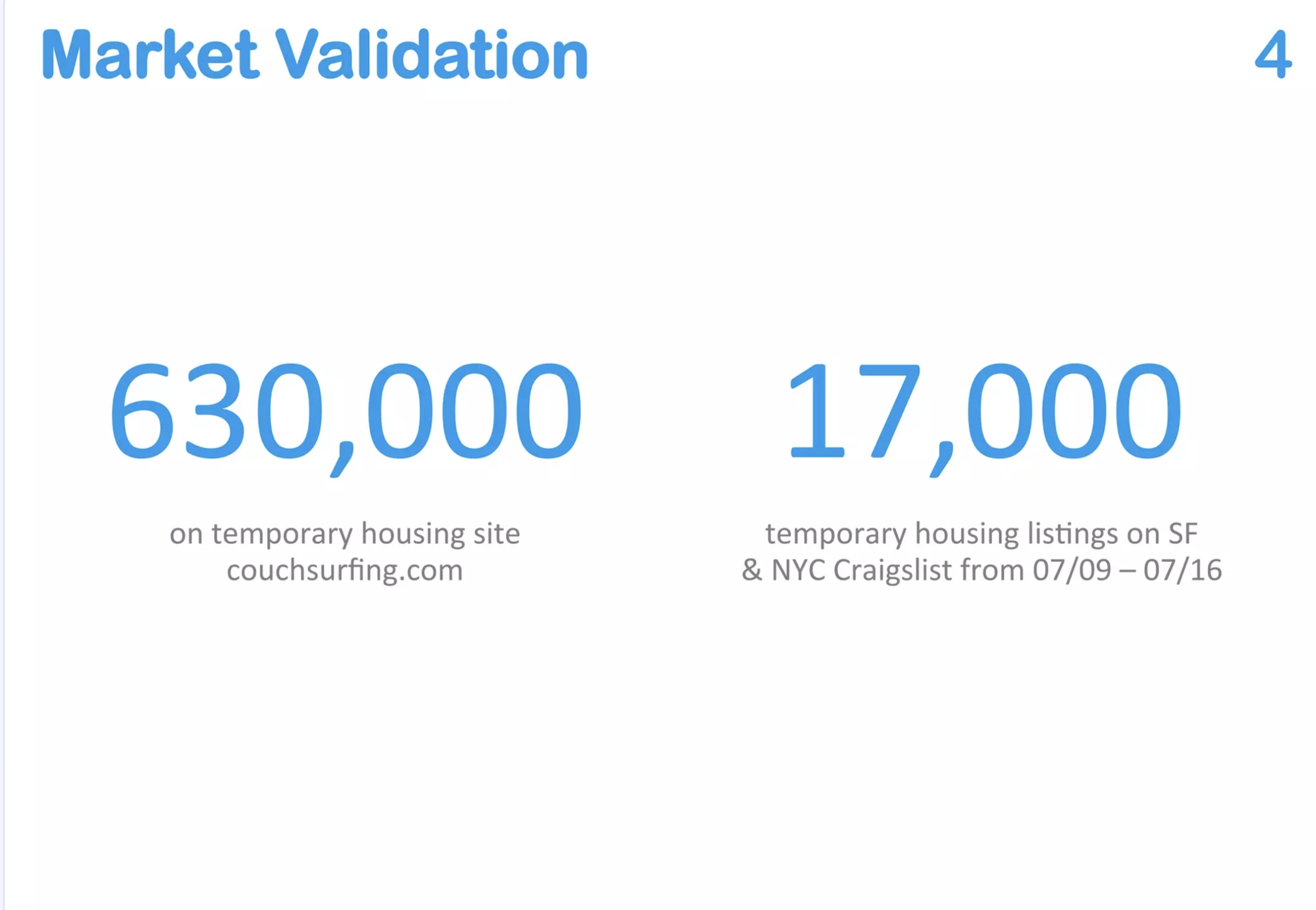

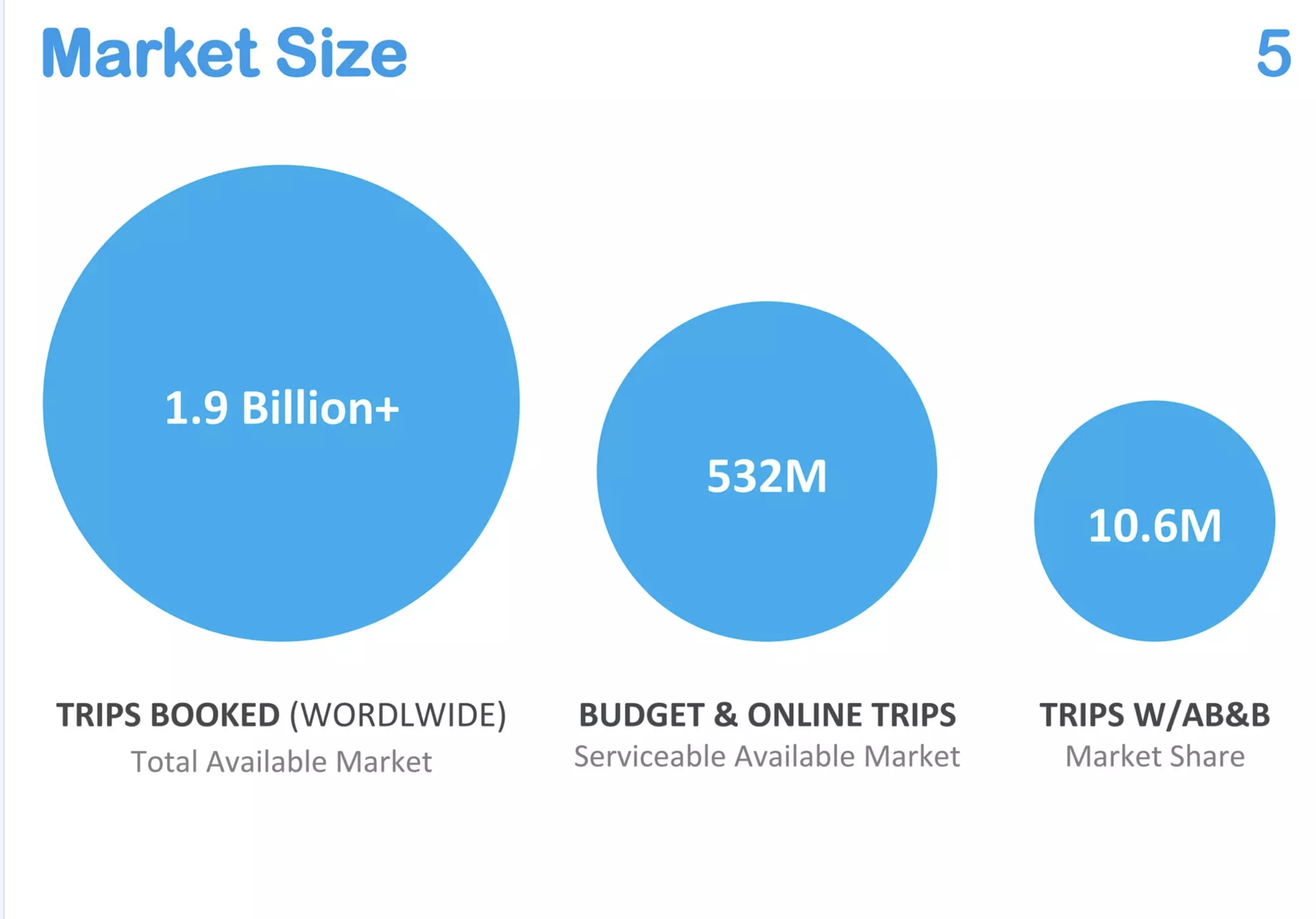

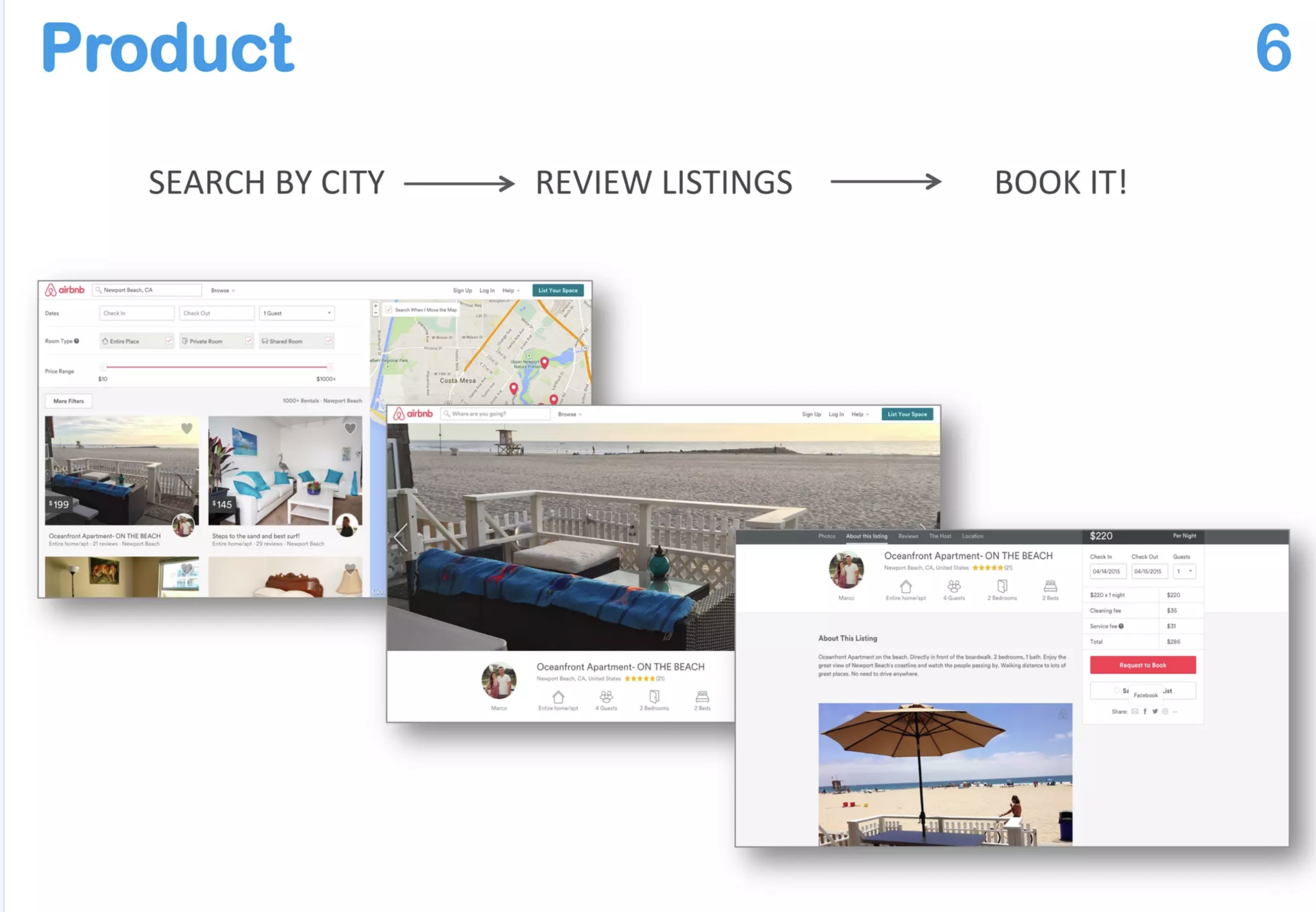

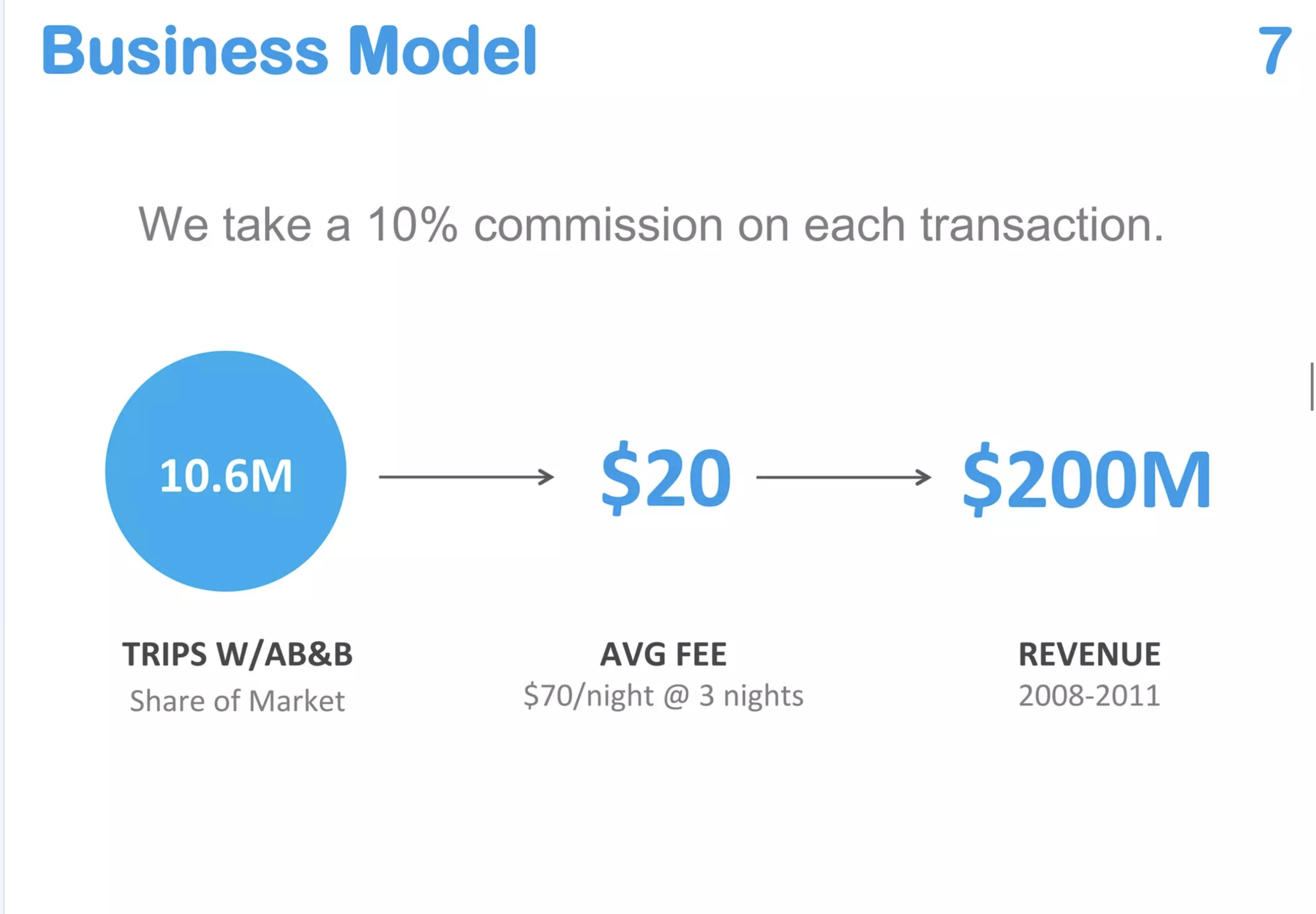

AirBnB

Dropbox

Inspiration and Advice

Components of a Winning Pitch Deck

Your pitch deck should be concise, no more than 10-12 slides, while effectively communicating your business idea and its potential. Here’s what you should include:

Title Slide

Start with a clear and catchy title that includes your company’s name and logo.

Problem

Clearly define the problem your product or service solves. Ensure it’s a problem worth solving.

Solution

Explain how your product or service solves the identified problem. Highlight what makes your solution unique and preferable.

Market Size

Provide evidence of the market size and potential growth. Y Combinator is looking for scalable businesses.

Business Model

Detail how you plan to make money. Be clear about your pricing strategy and revenue streams.

Traction

Show any evidence of growth, customer interest, or revenue. This demonstrates proof of concept and market demand.

Team

Introduce your team, highlighting each member’s expertise and why they’re the right person for the job. A strong team can significantly boost your chances.

Competition

Identify your main competitors and explain how your solution is better or different.

Financials

Include projections for the next 3-5 years. Be realistic but optimistic.

Ask

Conclude with what you’re asking from investors, whether it’s funding, mentorship, or both. Be specific about how you plan to use the resources.

Successful Startups

- Are capable of rapid growth

- Have a product that solves a real problem

- Are led by a strong, well-balanced team

- Show potential for scalability

- Have a clear and viable business model

Keeping these criteria in mind will guide you as you outline and flesh out your pitch deck.

Focus on clearly articulating the problem you’re solving, proving there’s a substantial market for your solution, and showcasing your team’s capability to execute the plan. Remember, investors are investing in your team as much as your idea.

To cater to different scenarios:

- For early-stage startups, emphasize the market opportunity and your team’s unique ability to capitalize on it. Highlight any traction or customer feedback you’ve received.

- For startups with solid traction, focus on metrics that prove market demand and detail your plan for scaling up, including how investors resources will aid in that process.

- For startups seeking to pivot or scale, demonstrate a clear understanding of your current position, why a pivot or scale is necessary, and how investors can facilitate this growth.

Key Components of a Successful Pitch

Before diving into examples, it’s vital to understand what makes a pitch successful. Key components include:

Clarity and Conciseness:

Clearly defining your product, market, and problem you’re solving. Investors review countless pitch decks. To ensure yours stands out, use simple, clear language and incorporate visuals like charts and images to convey your message effectively.

Unique Value Proposition:

Demonstrating what sets your startup apart from the competition. Your understanding of the problem and your unique solution are what set you apart. Detail the customer pain points and how your product solves these problems in a way that no other does.

Team Dynamics:

Showcasing the strength and balance of the founding team. Your team is your startup’s backbone. Highlight each member’s expertise, experience, and how they contribute to your startup’s success.

Growth Metrics:

Providing evidence of traction or potential for rapid growth. Traction is a key indicator of potential success. Include metrics such as user growth, revenue growth, or partnerships that demonstrate your startup’s momentum. Clearly articulate the size and characteristics of your target market. Investors need to see that there is a significant opportunity for growth.

Passion and Commitment:

Conveying a deep commitment to the problem you’re solving.

Now, let’s explore some examples of successful companies and what made them stand out.

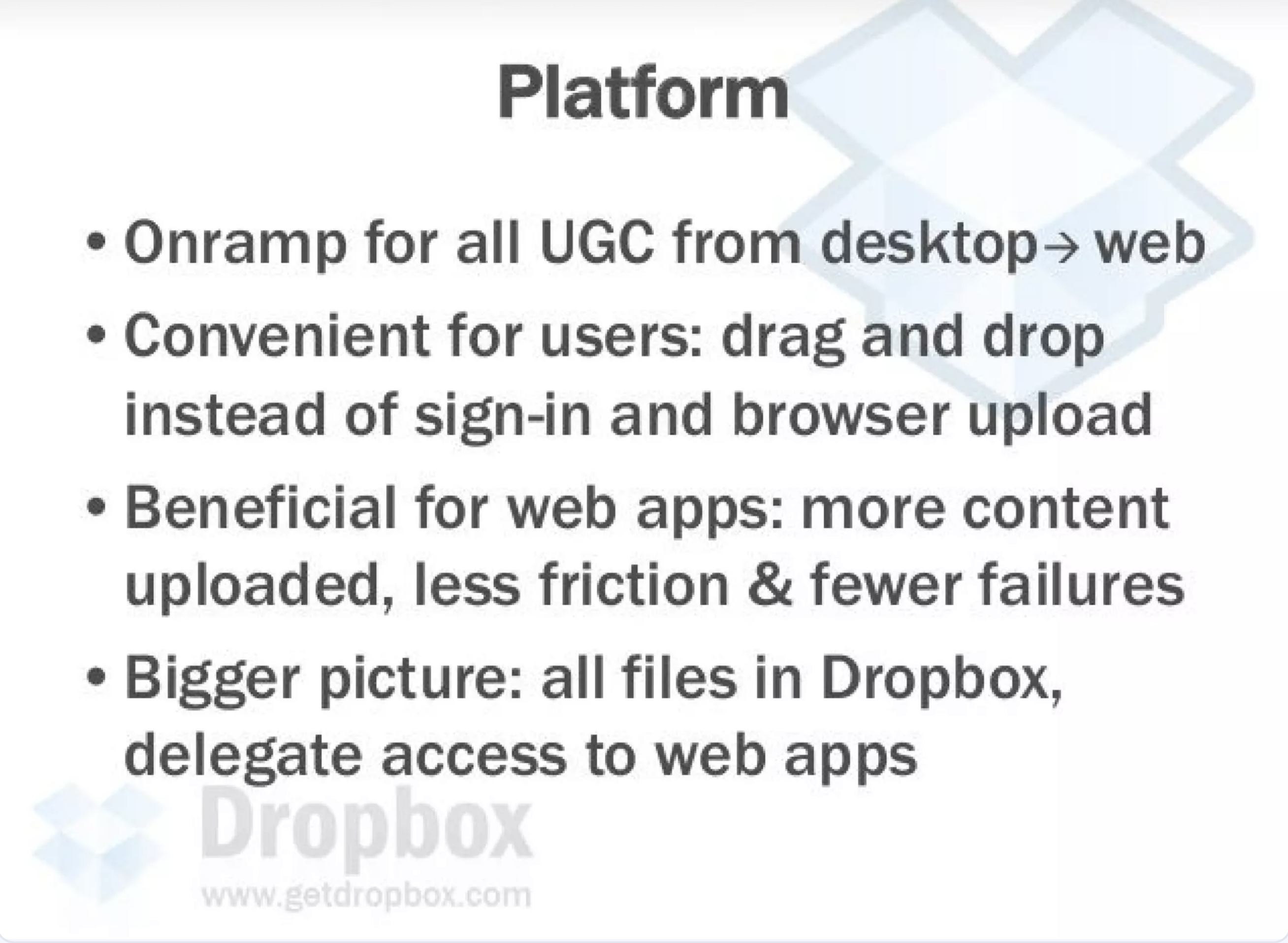

1. Dropbox

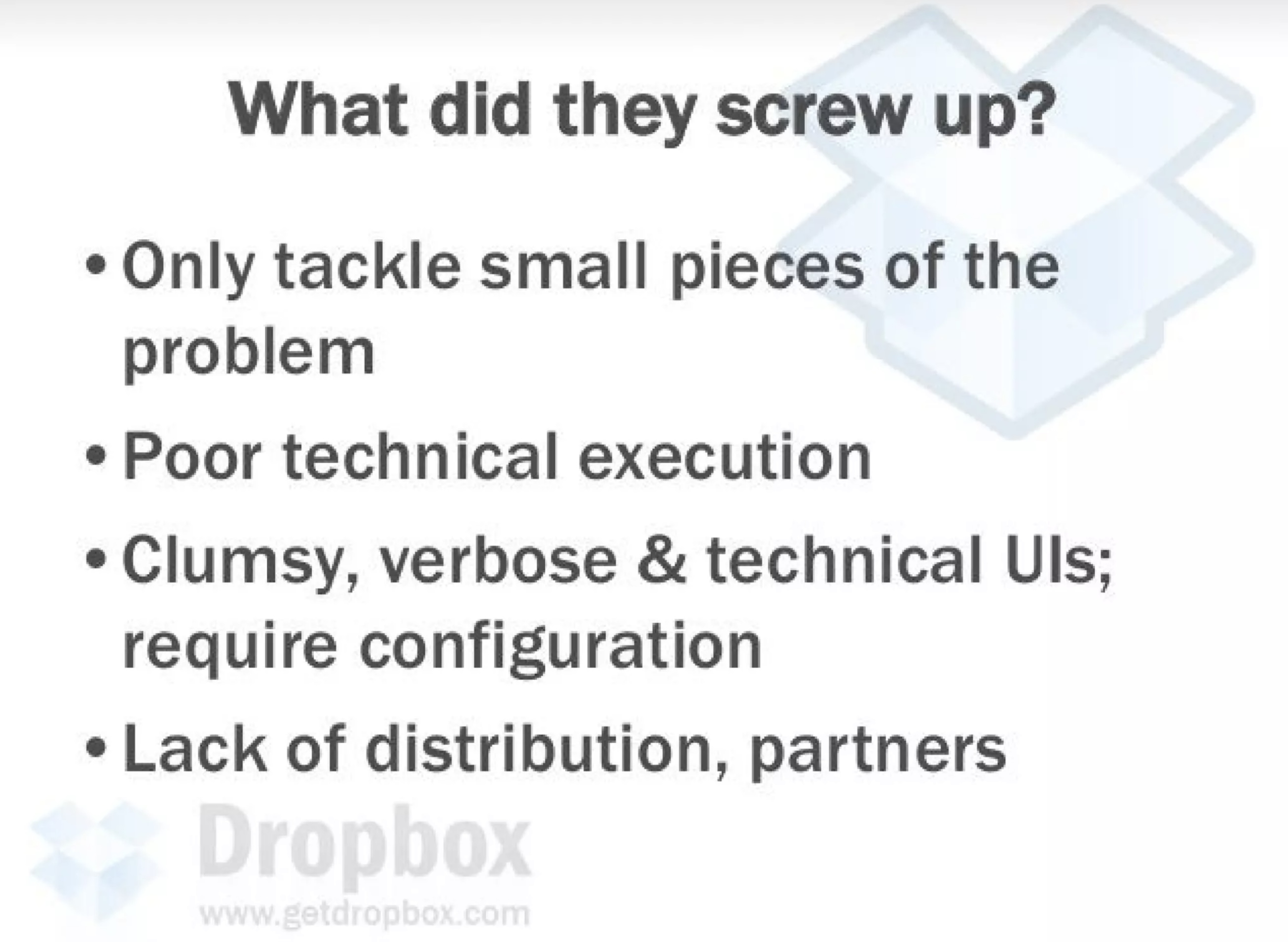

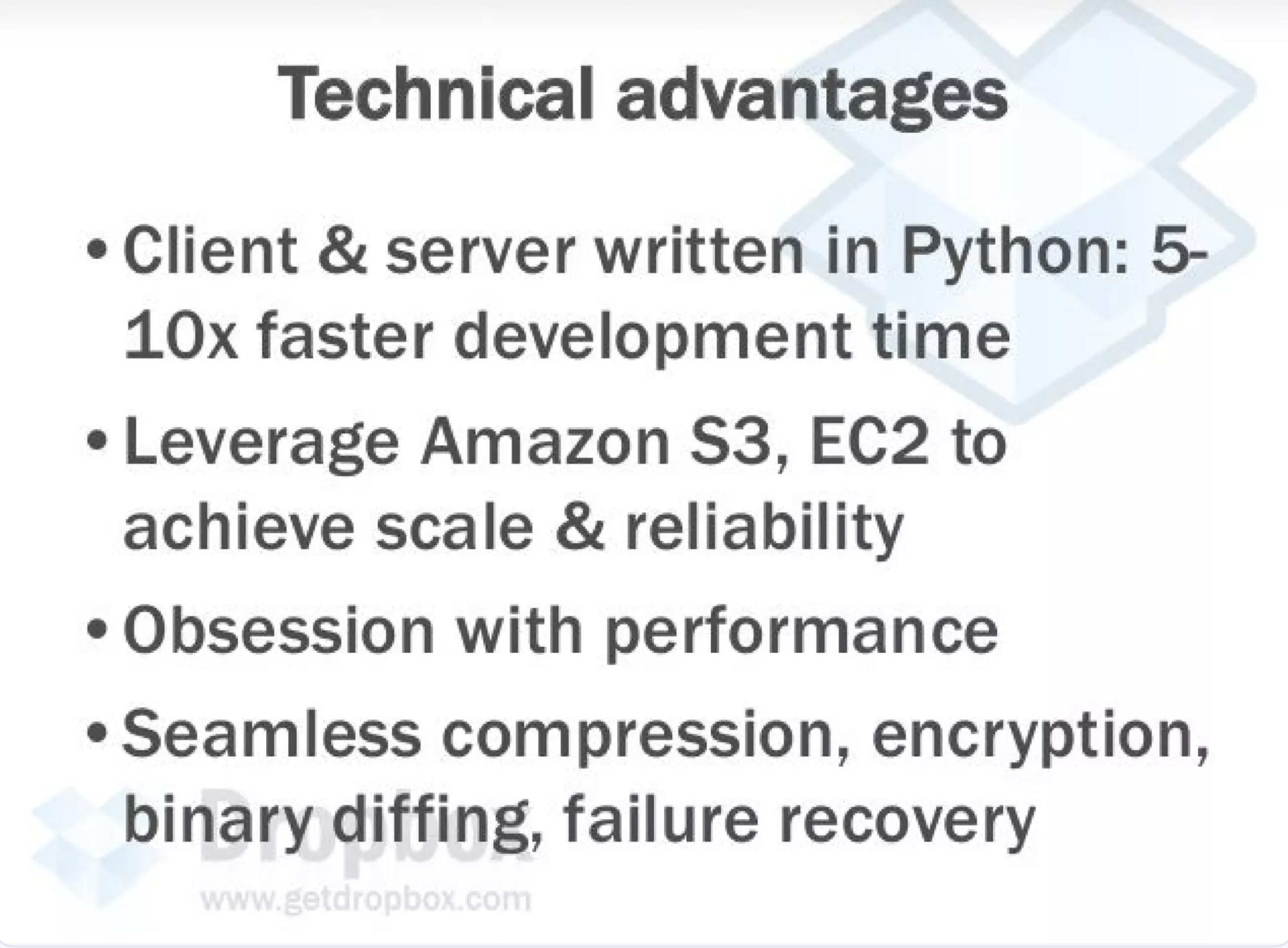

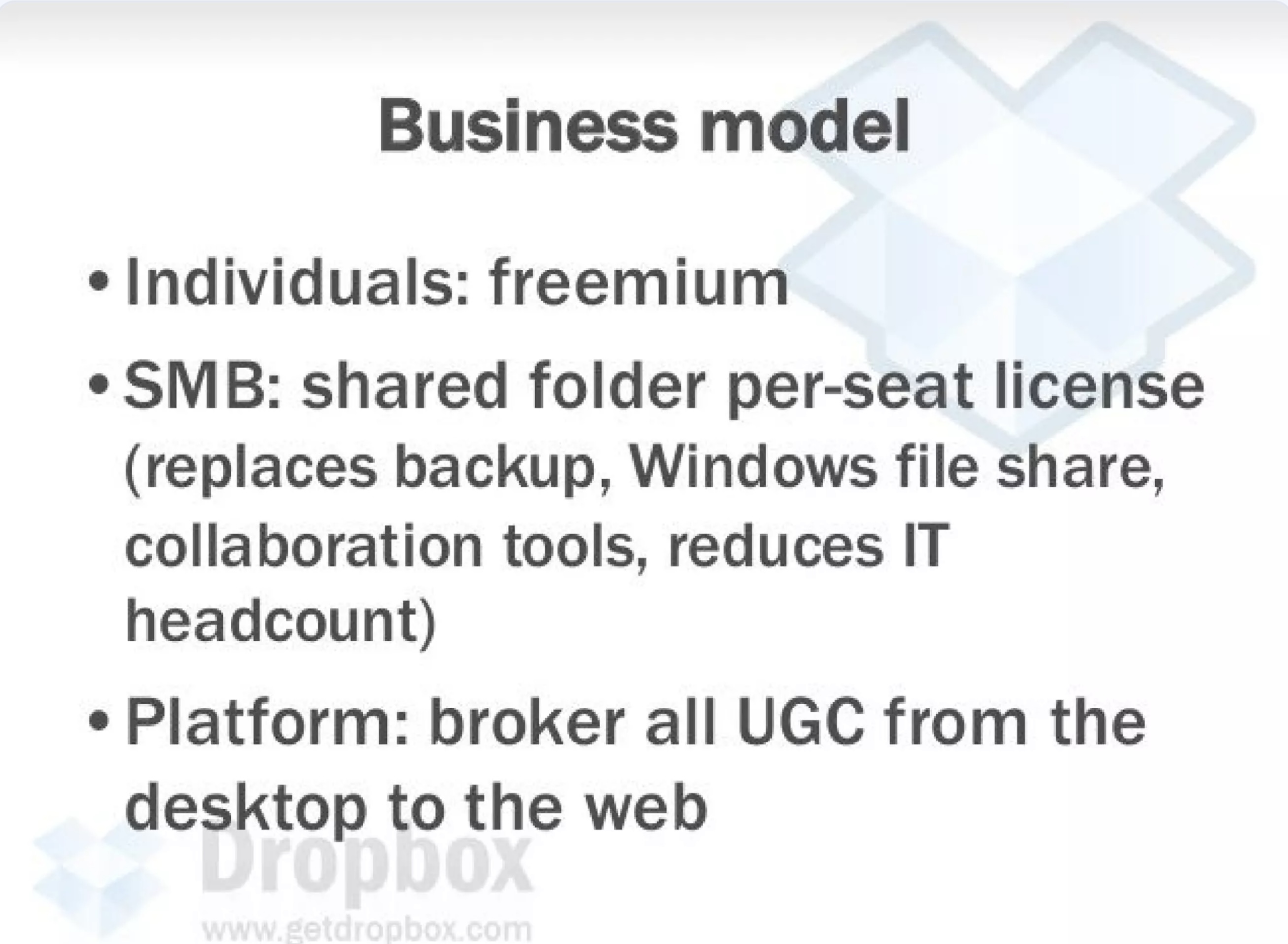

Dropbox was notable for its clarity in expressing the widespread issue of file storage and sharing across multiple devices. The team demonstrated a deep understanding of the problem and proposed a simple yet effective solution. Their pitch was boosted by the founder’s track record and the evident demand for the product.

Drew Houston was sitting on a bus from Boston to New York, and realized he’d forgotten his USB drive (again). Out of the frustration sparked innovation. What if there was a simpler way to store data that didn’t need to be in a physical format?

This simple inconvenience led to the creation of a service that would revolutionize file storage and sharing for millions.

Founded in 2007 by Houston and Arash Ferdowsi, Dropbox quickly became a game-changer in cloud storage. The company’s core service allows users to store, sync, and share files across devices seamlessly. With over 700 million registered users from 180 countries, Dropbox has grown from a simple file-sharing tool to a comprehensive collaboration platform.

Dropbox’s 2007 pitch deck, which secured a $1.2 million seed round, stands out for its clarity and engaging approach. The deck’s straightforward design, with large text and a clean layout, makes complex information easily digestible. It effectively tells a story, connecting investors to the common pain points of file sharing and storage.

Two aspects of the pitch deck particularly shine:

- Problem-solution narrative: the deck clearly outlines everyday file-sharing issues before presenting Dropbox as the elegant solution. This storytelling approach helps investors envision life without digital storage headaches.

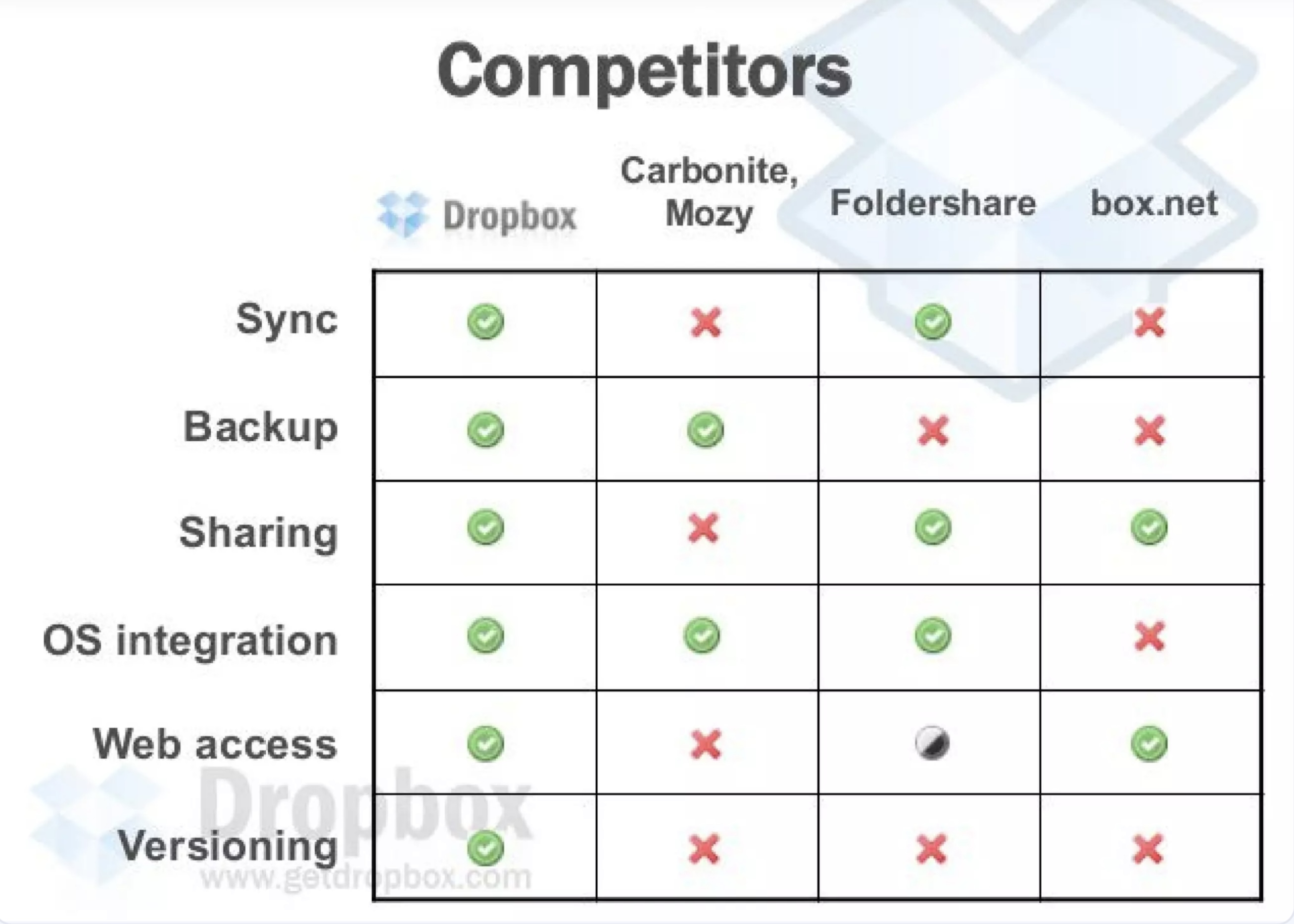

- Competitive edge visualization: Using a simple tick-and-cross system, Dropbox effectively illustrates its superiority over competitors. This visual comparison instantly communicates the product’s unique value proposition.

Favorite takeaway: Keep it simple and relatable. Dropbox’s pitch deck succeeds by addressing common problems with clear, jargon-free language. For entrepreneurs crafting their own pitch decks, remember that your audience may not be tech experts. Explain your solution in terms anyone can understand and appreciate.

2. Airbnb

Airbnb succeeded by illustrating a clear market need for affordable, short-term lodging solutions. The pitch stood out by showing early traction with users and a solid growth strategy. Their unique value proposition was effectively communicated through narratives of personal experiences.

Favorite takeaway: The intro. It’s all about hooking your audience. You need to describe your business using as few words as possible. Imagine telling a 5-year-old what your business is about. If you can’t do that, it’s time to put some time into nailing it down.

3. Stripe

Stripe impressed with their pitch by addressing a significant pain point – the complexity of online payments for businesses. They exhibited a profound technical understanding and a clear plan to simplify the online payment process for both companies and consumers.

4. Reddit

Reddit’s pitch highlighted the potential for a new kind of online community. The founders showcased their understanding of the potential for user-generated content and a strong commitment to growing their platform.

Key Takeaways from These Examples:

- Each successful pitch communicated a clear understanding of a significant problem and proposed a viable solution.

- Create traction or demonstrate strong potential for growth.

- Showcase a balanced and committed team capable of executing the plan.

For different use cases:

- Early-Stage Startups: Focus on articulating your unique solution to a big problem and the potential market. Emphasize any early traction or validation you have, no matter how small.

- Growth-Stage Startups: Highlight your growth metrics, customer feedback, and how you plan to scale further with investor's assistance.

- Non-tech Founders: Stress on the problem you are solving, market understanding, and why your team is uniquely positioned to succeed. Include any technical advisors or plans to build your tech team.

Pitching structure according to Sequoia

Company purpose

Start here: define your company in a single declarative sentence. This is harder than it looks. It’s easy to get caught up listing features instead of communicating your mission.

Problem

Describe the pain of your customer. How is this addressed today and what are the shortcomings to current solutions.

Solution

Explain your eureka moment. Why is your value prop unique and compelling? Why will it endure? And where does it go from here?

Why now?

The best companies almost always have a clear why now? Nature hates a vacuum—so why hasn’t your solution been built before now?

Market potential

Identify your customer and your market. Some of the best companies invent their own markets.

Competition / alternatives

Who are your direct and indirect competitors. Show that you have a plan to win.

Business model

How do you intend to thrive?

Team

Tell the story of your founders and key team members.

Financials

If you have any, please include.

Vision

If all goes well, what will you have built in five years?

Pitching structure according to YCombinator

Problem:

Identify the problem your product or service aims to solve.

Solution:

Showcase how your offering addresses the problem effectively.

Product:

Provide a clear description of your product or service.

Traction:

Highlight your achievements and metrics that indicate potential for growth.

Market Size:

Quantify the size of the opportunity your startup is targeting.

Business Model:

Explain how your startup will make money.

Team:

Introduce the team behind the idea and their qualifications.

Financials:

Outline your current financial situation and future projections.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Overloading slides with text: Keep information digestible and to the point.

- Ignoring the competition: Acknowledge other players in the market and explain how you differ.

- Unclear business model: Your path to revenue should be straightforward and realistic.

- Lack of clarity on use of funds: Be specific about how you plan to use investment capital.

Customer Segments

The Customer Segments Building Block defines the different groups of people or organizations an enterprise aims to reach and serve.

Customers comprise the heart of any business model. Without profitable customers, no company can survive for long. To better satisfy customers, a company may group them into distinct segments with common needs, behaviors, or other attributes. A business model may define one or several large or small Customer Segments. An organization must make a conscious decision about which segments to serve and which to ignore. Once this decision is made, a business model can be carefully designed around a strong understanding of specific customer needs.

Criteria for Separate Customer Segments

- Their needs require and justify a distinct offer

- They are reached through different Distribution Channels

- They require different types of relationships

- They have substantially different profitabilities

- They are willing to pay for different aspects of the offer

Key Questions

- For whom are we creating value?

- Who are our most important customers?

Types of Customer Segments

Mass Market

Business models focused on mass markets do not distinguish between different Customer Segments. The Value Propositions, Distribution Channels, and Customer Relationships all focus on one large group of customers with broadly similar needs and problems. This type of business model is often found in the consumer electronics sector.

Niche Market

Business models targeting niche markets cater to specific, specialized Customer Segments. The Value Propositions, Distribution Channels, and Customer Relationships are all tailored to the specific requirements of a niche market. Such business models are often found in supplier-buyer relationships. For example, many car part manufacturers depend heavily on purchases from major automobile manufacturers.

Segmented

Some business models distinguish between market segments with slightly different needs and problems. The retail arm of a bank like Credit Suisse, for example, may distinguish between a large group of customers, each possessing assets of up to U.S. \$100,000, and a smaller group of affluent clients, each of whose net worth exceeds U.S. \$500,000. Both segments have similar but varying needs and problems. This has implications for the other building blocks of Credit Suisse’s business model, such as the Value Proposition, Distribution Channels, Customer Relationships, and Revenue Streams. Consider Micro Precision Systems, which specializes in providing outsourced micromechanical design and manufacturing solutions. It serves three different Customer Segments — the watch industry, the medical industry, and the industrial automation sector — and offers each slightly different Value Propositions.

Diversified

An organization with a diversified customer business model serves two unrelated Customer Segments with very different needs and problems. For example, in 2006 Amazon.com decided to diversify its retail business by selling “cloud computing” services: online storage space and on-demand server usage. Thus, it started catering to a totally different Customer Segment — Web companies — with a totally different Value Proposition. The strategic rationale behind this diversification can be found in Amazon.com’s powerful IT infrastructure, which can be shared by its retail sales operations and the new cloud computing service unit.

Multi-sided Platforms (or Multi-sided Markets)

Some organizations serve two or more interdependent Customer Segments. A credit card company, for example, needs a large base of credit card holders and a large base of merchants who accept those credit cards. Similarly, an enterprise offering a free newspaper needs a large reader base to attract advertisers. On the other hand, it also needs advertisers to finance production and distribution. Both segments are required to make the business model work.

Value Propositions

The Value Propositions Building Block describes the bundle of products and services that create value for a specific Customer Segment.

The Value Proposition is the reason why customers turn to one company over another. It solves a customer problem or satisfies a customer need. Each Value Proposition consists of a selected bundle of products and/or services that caters to the requirements of a specific Customer Segment. In this sense, the Value Proposition is an aggregation, or bundle, of benefits that a company offers customers.

Some Value Propositions may be innovative and represent a new or disruptive offer. Others may be similar to existing market offers, but with added features and attributes.

Key Questions

- What value do we deliver to the customer?

- Which one of our customer’s problems are we helping to solve?

- Which customer needs are we satisfying?

- What bundles of products and services are we offering to each Customer Segment?

A Value Proposition creates value for a Customer Segment through a distinct mix of elements catering to that segment’s needs. Values may be quantitative (e.g. price, speed of service) or qualitative (e.g. design, customer experience).

Elements from the following non-exhaustive list can contribute to customer value creation.

Newness

Some Value Propositions satisfy an entirely new set of needs that customers previously didn’t perceive because there was no similar offering. This is often, but not always, technology related. Cell phones, for instance, created a whole new industry around mobile telecommunication. On the other hand, products such as ethical investment funds have little to do with new technology.

Performance

Improving product or service performance has traditionally been a common way to create value. The PC sector has traditionally relied on this factor by bringing more powerful machines to market. But improved performance has its limits. In recent years, for example, faster PCs, more disk storage space, and better graphics have failed to produce corresponding growth in customer demand.

Customization

Tailoring products and services to the specific needs of individual customers or Customer Segments creates value. In recent years, the concepts of mass customization and customer co-creation have gained importance. This approach allows for customized products and services, while still taking advantage of economies of scale.

“Getting the Job Done”

Value can be created simply by helping a customer get certain jobs done. Rolls-Royce understands this very well: its airline customers rely entirely on Rolls-Royce to manufacture and service their jet engines. This arrangement allows customers to focus on running their airlines. In return, the airlines pay Rolls-Royce a fee for every hour an engine runs.

Design

Design is an important but difficult element to measure. A product may stand out because of superior design. In the fashion and consumer electronics industries, design can be a particularly important part of the Value Proposition.

Brand/Status

Customers may find value in the simple act of using and displaying a specific brand. Wearing a Rolex watch signifies wealth, for example. On the other end of the spectrum, skateboarders may wear the latest “underground” brands to show that they are “in.”

Price

Offering similar value at a lower price is a common way to satisfy the needs of price-sensitive Customer Segments. But low-price Value Propositions have important implications for the rest of a business model. No-frills airlines, such as Southwest, easyJet, and Ryanair have designed entire business models specifically to enable low-cost air travel. Another example of a price-based Value Proposition can be seen in the Nano, a new car designed and manufactured by the Indian conglomerate Tata. Its surprisingly low price makes the automobile affordable to a whole new segment of the Indian population. Increasingly, free offers are starting to permeate various industries. Free offers range from free newspapers to free e-mail, free mobile phone services, and more.

Cost Reduction

Helping customers reduce costs is an important way to create value. Salesforce.com, for example, sells a hosted Customer Relationship Management (CRM) application. This relieves buyers from the expense and trouble of having to buy, install, and manage CRM software themselves.

Risk Reduction

Customers value reducing the risks they incur when purchasing products or services. For a used car buyer, a one-year service guarantee reduces the risk of post-purchase breakdowns and repairs. A service-level guarantee partially reduces the risk undertaken by a purchaser of outsourced IT services.

Accessibility

Making products and services available to customers who previously lacked access to them is another way to create value. This can result from business model innovation, new technologies, or a combination of both. NetJets, for instance, popularized the concept of fractional private jet ownership. Using an innovative business model, NetJets offers individuals and corporations access to private jets, a service previously unaffordable to most customers. Mutual funds provide another example of value creation through increased accessibility. This innovative financial product made it possible even for those with modest wealth to build diversified investment portfolios.

Convenience/Usability

Making things more convenient or easier to use can create substantial value. With iPod and iTunes, Apple offered customers unprecedented convenience searching, buying, downloading, and listening to digital music. It now dominates the market.

Channels

The Channels Building Block describes how a company communicates with and reaches its Customer Segments to deliver a Value Proposition. Communication, distribution, and sales Channels comprise a company's interface with customers. Channels are customer touch points that play an important role in the customer experience. Channels serve several functions, including:

- Raising awareness among customers about a company’s products and services

- Helping customers evaluate a company’s Value Proposition

- Allowing customers to purchase specific products and services

- Delivering a Value Proposition to customers

- Providing post-purchase customer support

Key Questions

- Through which Channels do our Customer Segments want to be reached?

- How are we reaching them now?

- How are our Channels integrated?

- Which ones work best?

- Which ones are most cost-efficient?

- How are we integrating them with customer routines?

Channel Phases

Channels have five distinct phases. Each channel can cover some or all of these phases. We can distinguish between direct Channels and indirect ones, as well as between owned Channels and partner Channels.

Finding the right mix of Channels to satisfy how customers want to be reached is crucial in bringing a Value Proposition to market. An organization can choose between reaching its customers through its own Channels, through partner Channels, or through a mix of both.

| Channel Phases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Channel Types | 1. Awareness | 2. Evaluation | 3. Purchase | 4. Delivery | 5. After sales | |

| Own | Sales force | How do we raise awareness about our company's products and services? | How do we help customers evaluate our organization's Value Proposition? | How do we allow customers to purchase specific products and services? | How do we deliver a Value Proposition to customers? | How do we provide post-purchase customer support? |

| Web sales | ||||||

| Own stores | ||||||

| Partner | Partner stores | |||||

| Wholesaler | ||||||

Owned vs. Partner Channels

Owned Channels can be direct, such as an in-house sales force or a website, or they can be indirect, such as retail stores owned or operated by the organization. Partner Channels are indirect and span a whole range of options, such as wholesale distribution, retail, or partner-owned websites.

Partner Channels lead to lower margins, but they allow an organization to expand its reach and benefit from partner strengths. Owned Channels, particularly direct ones, have higher margins, but can be costly to put in place and to operate. The trick is to find the right balance between the different types of Channels, to integrate them in a way to create a great customer experience, and to maximize revenues.

Customer Relationships

The Customer Relationships Building Block describes the types of relationships a company establishes with specific Customer Segments. A company should clarify the type of relationship it wants to establish with each Customer Segment. Relationships can range from personal to automated. Customer relationships may be driven by the following motivations:

- Customer acquisition

- Customer retention

- Boosting sales (upselling)

In the early days, for example, mobile network operator Customer Relationships were driven by aggressive acquisition strategies involving free mobile phones. When the market became saturated, operators switched to focusing on customer retention and increasing average revenue per customer.

The Customer Relationships called for by a company’s business model deeply influence the overall customer experience.

Key Questions

- What type of relationship does each of our Customer Segments expect us to establish and maintain with them?

- Which ones have we established?

- How costly are they?

- How are they integrated with the rest of our business model?

Types of Customer Relationships

- Personal assistance: This relationship is based on human interaction. The customer can communicate with a real customer representative to get help during the sales process or after the purchase is complete. This may happen on-site at the point of sale, through call centers, by e-mail, or through other means.

- Dedicated personal assistance: This relationship involves dedicating a customer representative specifically to an individual client. It represents the deepest and most intimate type of relationship and normally develops over a long period of time. In private banking services, for example, dedicated bankers serve high net worth individuals. Similar relationships can be found in other businesses in the form of key account managers who maintain personal relationships with important customers.

- Self-service: In this type of relationship, a company maintains no direct relationship with customers. It provides all the necessary means for customers to help themselves.

- Automated services: This type of relationship mixes a more sophisticated form of customer self-service with automated processes. For example, personal online profiles give customers access to customized services. Automated services can recognize individual customers and their characteristics and offer information related to orders or transactions. At their best, automated services can stimulate a personal relationship (e.g., offering book or movie recommendations).

- Communities: Increasingly, companies are utilizing user communities to become more involved with customers/prospects and to facilitate connections between community members. Many companies maintain online communities that allow users to exchange knowledge and solve each other’s problems. Communities can also help companies better understand their customers. Pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline launched a private online community when it introduced alli, a new prescription-free weight-loss product to increase its understanding of customer challenges.

- Co-creation: More companies are going beyond the traditional customer-vendor relationship to co-create value with customers. Amazon.com invites customers to write reviews and thus create value for other book lovers. Some companies engage customers to assist with the design of new and innovative products. Others, such as YouTube.com, solicit customers to create content for public consumption.

Revenue Streams

The Revenue Streams Building Block represents the cash a company generates from each Customer Segment (costs must be subtracted from revenues to create earnings).

If customers comprise the heart of a business model, Revenue Streams are its arteries. A company must ask itself, For what value is each Customer Segment truly willing to pay? Successfully answering that question allows the firm to generate one or more Revenue Streams from each Customer Segment. Each Revenue Stream may have different pricing mechanisms, such as fixed list prices, bargaining, auctioning, market dependent, volume dependent, or yield management.

Each Revenue Stream might have different pricing mechanisms.

The type of pricing mechanism chosen can make a big difference in terms of revenues generated. There are two main types of pricing mechanisms:

- Fixed Pricing: The price is set and does not change regardless of demand or supply.

- Dynamic Pricing: The price can fluctuate based on demand, supply, or other factors, allowing for adjustments to maximize revenue.

A business model can involve two different types of Revenue Streams:

- Transaction revenues resulting from one-time customer payments

- Recurring revenues resulting from ongoing payments to either deliver a Value Proposition to customers or provide post-purchase customer support

Questions to consider:

- For what value are our customers really willing to pay?

- For what do they currently pay?

- How are they currently paying?

- How would they prefer to pay?

- How much does each Revenue Stream contribute to overall revenues?

There are several ways to generate Revenue Streams:

Asset Sale

The most widely understood Revenue Stream derives from selling ownership rights to a physical product. For example, Amazon.com sells books, music, consumer electronics, and more online. Fiat sells automobiles, which buyers are free to drive, resell, or even destroy.

Usage Fee

This Revenue Stream is generated by the use of a particular service. The more a service is used, the more the customer pays. Examples include:

- A telecom operator charging customers for the number of minutes spent on the phone.

- A hotel charging customers for the number of nights rooms are used.

- A package delivery service charging customers for the delivery of a parcel from one location to another.

Subscription Fees

This Revenue Stream is generated by selling continuous access to a service. Examples include:

- A gym selling its members monthly or yearly subscriptions for access to exercise facilities.

- World of Warcraft Online, a Web-based computer game, allowing users to play its online game in exchange for a monthly subscription fee.

- Nokia’s Comes with Music service giving users access to a music library for a subscription fee.

Lending/Renting/Leasing

This Revenue Stream is created by temporarily granting someone the exclusive right to use a particular asset for a fixed period in return for a fee. Examples include:

- Zipcar.com providing a service that allows customers to rent cars by the hour in North American cities.

Licensing

This Revenue Stream is generated by giving customers permission to use protected intellectual property in exchange for licensing fees. Examples include:

- Licensing in the media industry where content owners retain copyright while selling usage licenses to third parties.

- In technology sectors, patentholders granting other companies the right to use a patented technology in return for a license fee.

Brokerage Fees

This Revenue Stream derives from intermediation services performed on behalf of two or more parties. Examples include:

- Credit card providers earning revenues by taking a percentage of the value of each sales transaction executed between credit card merchants and customers.

- Brokers and real estate agents earning a commission each time they successfully match a buyer and seller.

Advertising

This Revenue Stream results from fees for advertising a particular product, service, or brand. Traditionally, the media industry and event organizers relied heavily on revenues from advertising. In recent years, other sectors, including software and services, have started relying more heavily on advertising revenues.

Pricing Mechanisms

| Fixed

"Menu" Pricing Predefined prices are based on static variables |

Dynamic Pricing Prices change based on market conditions |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| List price | Fixed prices for individual products, services, or other Value Propositions |

Negotiation (bargaining) |

Price negotiated between two or more partners depending on negotiation power and/or negotiation skills |

| Product feature dependent | Price depends on the number or quality of Value Proposition features | Yield management | Price depends on inventory and time of purchase (normally used for perishable resources such as hotel rooms or airline seats) |

| Customer segment dependent | Price depends on the type and characteristic of a Customer Segment | Real-time-market | Price is established dynamically based on supply and demand |

| Volume dependent | Price as a function of the quantity purchased | Auctions | Price determined by outcome of competitive bidding |

Key Resources

The Key Resources Building Block describes the most important assets required to make a business model work.

Every business model requires Key Resources. These resources allow an enterprise to create and offer a Value Proposition, reach markets, maintain relationships with Customer Segments, and earn revenues. Different Key Resources are needed depending on the type of business model. A microchip manufacturer requires capital-intensive production facilities, whereas a microchip designer focuses more on human resources.

Key resources can be physical, financial, intellectual, or human. Key resources can be owned or leased by the company or acquired from key partners.

What Key Resources do our Value Propositions require? Our Distribution Channels? Customer Relationships? Revenue Streams?

Key Resources can be categorized as follows:

Physical

This category includes physical assets such as manufacturing facilities, buildings, vehicles, machines, systems, point-of-sales systems, and distribution networks. Examples include:

- Retailers like Wal-Mart and Amazon.com rely heavily on physical resources, which are often capital-intensive.

- Wal-Mart has an enormous global network of stores and related logistics infrastructure.

- Amazon.com has an extensive IT, warehouse, and logistics infrastructure.

Intellectual

Intellectual resources such as brands, proprietary knowledge, patents and copyrights, partnerships, and customer databases are increasingly important components of a strong business model. Examples include:

- Consumer goods companies like Nike and Sony rely heavily on brand as a Key Resource.

- Microsoft and SAP depend on software and related intellectual property developed over many years.

- Qualcomm, a designer and supplier of chipsets for broadband mobile devices, built its business model around patented microchip designs that earn the company substantial licensing fees.

Human

Every enterprise requires human resources, but people are particularly prominent in certain business models. For example, human resources are crucial in knowledge-intensive and creative industries. An example includes:

- A pharmaceutical company such as Novartis, which relies heavily on human resources: its business model is predicated on an army of experienced scientists and a large and skilled sales force.

Financial

Some business models call for financial resources and/or financial guarantees, such as cash, lines of credit, or a stock option pool for hiring key employees. An example includes:

- Ericsson, the telecom manufacturer, uses financial resource leverage within its business model. Ericsson may opt to borrow funds from banks and capital markets, then use a portion of the proceeds to provide vendor financing to equipment customers, ensuring that orders are placed with Ericsson rather than competitors.

Key Activities

The Key Activities Building Block describes the most important things a company must do to make its business model work.

Every business model calls for a number of Key Activities. These are the most important actions a company must take to operate successfully. Like Key Resources, they are required to create and offer a Value Proposition, reach markets, maintain Customer Relationships, and earn revenues. And like Key Resources, Key Activities differ depending on business model type. For software maker Microsoft, Key Activities include software development. For PC manufacturer Dell, Key Activities include supply chain management. For consultancy McKinsey, Key Activities include problem solving.

What Key Activities do our Value Propositions require? Our Distribution Channels? Customer Relationships? Revenue Streams?

Key Activities can be categorized as follows:

Production

These activities relate to designing, making, and delivering a product in substantial quantities and/or of superior quality. Production activity dominates the business models of manufacturing firms.

Problem Solving

Key Activities of this type relate to coming up with new solutions to individual customer problems. The operations of consultancies, hospitals, and other service organizations are typically dominated by problem-solving activities. Their business models call for activities such as knowledge management and continuous training.

Platform/Network

Business models designed with a platform as a Key Resource are dominated by platform or network-related Key Activities. Examples include:

- eBay’s business model requires the company to continually develop and maintain its platform: the website at eBay.com.

- Visa’s business model requires activities related to its Visa® credit card transaction platform for merchants, customers, and banks.

- Microsoft’s business model requires managing the interface between other vendors’ software and its Windows® operating system platform.

Key Activities in this category relate to platform management, service provisioning, and platform promotion.

Key Partnerships

The Key Partnerships Building Block describes the network of suppliers and partners that make the business model work.

Companies forge partnerships for many reasons, and partnerships are becoming a cornerstone of many business models. Companies create alliances to optimize their business models, reduce risk, or acquire resources.

We can distinguish between four different types of partnerships:

- Strategic alliances between non-competitors

- Coopetition: strategic partnerships between competitors

- Joint ventures to develop new businesses

- Buyer-supplier relationships to assure reliable supplies

Questions to consider:

- Who are our Key Partners?

- Who are our key suppliers?

- Which Key Resources are we acquiring from partners?

- Which Key Activities do partners perform?

It can be useful to distinguish between three motivations for creating partnerships:

Optimization and Economy of Scale

The most basic form of partnership or buyer-supplier relationship is designed to optimize the allocation of resources and activities. It is illogical for a company to own all resources or perform every activity by itself. Optimization and economy of scale partnerships are usually formed to reduce costs and often involve outsourcing or sharing infrastructure.

Reduction of Risk and Uncertainty

Partnerships can help reduce risk in a competitive environment characterized by uncertainty. An example is Blu-ray, an optical disc format jointly developed by a group of the world’s leading consumer electronics, personal computer, and media manufacturers. The group cooperated to bring Blu-ray technology to market, yet individual members compete in selling their own Blu-ray products.

Acquisition of Particular Resources and Activities

Few companies own all the resources or perform all the activities described by their business models. Rather, they extend their own capabilities by relying on other firms to furnish particular resources or perform certain activities. Examples include:

- A mobile phone manufacturer licensing an operating system for its handsets rather than developing one in-house.

- An insurer relying on independent brokers to sell its policies rather than developing its own sales force.

Cost Structure

The Cost Structure describes all costs incurred to operate a business model.

This building block describes the most important costs incurred while operating under a particular business model. Creating and delivering value, maintaining Customer Relationships, and generating revenue all incur costs. Such costs can be calculated relatively easily after defining Key Resources, Key Activities, and Key Partnerships. Some business models, though, are more cost-driven than others. So-called “no frills” airlines, for instance, have built business models entirely around low Cost Structures.

Questions to consider:

- What are the most important costs inherent in our business model?

- Which Key Resources are most expensive?

- Which Key Activities are most expensive?

Cost Structures can be classified as:

Cost-driven

Cost-driven business models focus on minimizing costs wherever possible. This approach aims at creating and maintaining the leanest possible Cost Structure, using low price Value Propositions, maximum automation, and extensive outsourcing. Examples include:

- No frills airlines, such as Southwest, easyJet, and Ryanair, typify cost-driven business models.

Value-driven

Some companies are less concerned with the cost implications of a particular business model design and instead focus on value creation. Premium Value Propositions and a high degree of personalized service usually characterize value-driven business models. An example includes:

- Luxury hotels, with their lavish facilities and exclusive services.

Cost Structures can have the following characteristics:

Fixed Costs

Costs that remain the same despite the volume of goods or services produced. Examples include:

- Salaries

- Rents

- Physical manufacturing facilities

Some businesses, such as manufacturing companies, are characterized by a high proportion of fixed costs.

Variable Costs

Costs that vary proportionally with the volume of goods or services produced. Examples include:

- Music festivals, which are characterized by a high proportion of variable costs.

Economies of Scale

Cost advantages that a business enjoys as its output expands. Examples include:

- Larger companies benefit from lower bulk purchase rates. This and other factors cause average cost per unit to fall as output rises.

Economies of Scope

Cost advantages that a business enjoys due to a larger scope of operations. Examples include:

- In a large enterprise, the same marketing activities or Distribution Channels may support multiple products.

The Importance of Network Effects

Introduction to Network Effects

Understanding network effects is crucial in today's digital age where the success of platforms such as social media, marketplaces, and communication tools often depend on them. Network effects occur when a product or service gains additional value as more people use it. This set of notes is designed to offer a comprehensive insight into the concept of network effects, its dynamics, and how businesses can leverage them to enhance value.

What are Network Effects?

Network effects refer to the phenomenon where the value of a product or service increases with the number of users. It is a key driver of the growth and sustainability of platforms and is often fundamental to their success.

Key Characteristics of Network Effects

- Value Increase: The utility of the network improves for all users as more individuals join.

- Positive Feedback Loop: Success breeds success; more users attract even more users.

- Lock-in Effect: As the network grows, users become more locked in due to increased switching costs.

Types of Network Effects

Direct Network Effects

Direct network effects occur when the value of a service increases directly as more people use the same service. For example, a social media platform becomes more valuable when your friends and family join, allowing for richer interaction.

Indirect Network Effects

Indirect network effects happen when an increase in users of one product leads to increased value for a complementary product. An example is an operating system that becomes more valuable as more software applications are developed for it.

Two-Sided Network Effects

These occur in markets with two distinct user groups, such as buyers and sellers on a marketplace platform. The platform becomes more valuable as the number of participants in each group increases.

Dynamics of Network Effects

How do Network Effects Create Value?

- User Growth: Increased users lead to more data points, enhancing analytics and targeted services.

- Scalability: Platforms can scale rapidly with little incremental cost, increasing profit margins.

- Innovation: Larger networks can attract developers and new business models, fostering innovation.

Challenges Associated with Network Effects

- Vulnerability to Competition: New players can disrupt established networks by offering superior features or ease of use.

- Overcrowding: Excessive users can lead to negative outcomes such as reduced service quality.

- Control and Moderation: Managing large user bases involves challenges around controlling content and maintaining community standards.

Strategies for Harnessing Network Effects

How Can Businesses Utilize Network Effects?

- Build a Strong Base: Start by focusing on acquiring a critical mass of core users to ignite the network effect.

- Encourage Engagement: Develop features that promote interaction and engagement among users.

- Foster Partnerships: Collaborate with complementary platforms or services to strengthen indirect network effects.

- Ensure Quality: Maintain, moderate, and elevate service quality to prevent user disillusionment.

- Leverage Data: Use user-generated data to enhance product offerings and personalize services.

Case Studies and Real-World Examples

- Social Media Platforms: Facebook and Twitter demonstrate direct network effects where increased user participation directly boosts value.

- Marketplaces: eBay and Amazon benefit from both direct and two-sided network effects, as more buyers and sellers join the platforms.

- Ride-Sharing Services: Uber and Lyft rely on two-sided network effects between drivers and riders to drive growth and value.

Conclusion

Network effects are a fundamental aspect of the modern economic and technological landscape. By understanding and leveraging these dynamics, businesses can drive significant value creation, establish competitive advantages, and foster innovation. Recognizing the intricacies of direct, indirect, and two-sided network effects enables strategic planning and sustainable platform growth.

Uses of Network Effects

Why Do Network Effects Matter?

When a startup successfully establishes strong network effects, it can reap benefits such as exponential growth, defensibility against competitors, increased user loyalty, and in some cases even market domination. These effects can transform a small company into a near-monopoly in certain services or verticals.

- Network effects drive organic user growth and diminish customer acquisition costs over time.

- The more members join, the more defensible the platform’s position in the market, creating a moat.

- Product improvements can become cheaper as more and more users contribute to content generation or data feedback loops.

Key Properties and Dynamics of Networks

Nodes, Links, and Clusters

Every network can be broken down into fundamental components. Understanding these components helps founders recognize how relationships form, strengthen, and sometimes decay.

- Nodes (or Users): These are the individual participants, entities, or points of data in the network.

- Links (or Connections): The pathways through which nodes interact (friend connections on social media, buyer-seller transactions, communication channels).

- Clusters (or Sub-networks): Groups of nodes that are more densely connected to each other than to the rest of the network. They help demonstrate how network effects can initially build within a niche before spreading outwards.

Connection Mechanisms and Flow

To create or amplify network effects, you must understand how nodes connect and how information or value flows within a network. Different platforms may emphasize different mechanisms, such as sharing, messaging, or transactions.

- One-to-One Connections: Person-to-person messages in a chat app.

- One-to-Many Connections: Posting content on social media to followers.

- Many-to-Many Connections: Discussion forums or peer-to-peer marketplaces where any participant can interact with any other.

When value or information flows smoothly and efficiently, users perceive significant value, creating a virtuous cycle of growth.

Growth Patterns and Phases

Networks rarely grow linearly; they usually follow distinct inflection points, from a small cluster (early adopters) to mass adoption. Founders must strategize during each stage to ensure continued traction.

- Seed Phase: Convince a small group of distinct users (e.g., experts or enthusiasts) to join and actively engage, creating initial value.

- Expansion Phase: Demonstrate broader appeal and utility, leverage early adopters to attract new users, and refine product features that highlight network-driven benefits.

- Scaling Phase: Achieve rapid snowballing effect. Word-of-mouth, viral loops, or platform-specific referral programs drive organic growth.

- Maintenance and Renewal: Retain users through ongoing value, adapt to changing user preferences, and continue increasing value for existing and new members.

Enabling Factors for Network Effects

Technology Layer

The technology stack and infrastructure are critical in enabling network effects. Without a robust architecture, platforms might fail under increased user loads, stifling growth.

- Scalability: Systems must handle large, sudden inflows of users.

- Interoperability: Integration with other complementary platforms can spur indirect network effects.

- Security and Reliability: Trust is paramount. Users and businesses rely on the platform for communication, transactions, etc.

Product Design Strategies

Thoughtful design choices enhance the viral and sticky nature of a platform. A product that seamlessly encourages user-to-user interactions or fosters a sense of community can unlock exponential network growth.

- Onboarding Flow: Make it easy for new users to invite friends, connect with contacts, or engage in content creation.

- Retention Hooks: Notifications, user-generated content, or support communities that drive recurring usage.

- Feedback Loops: Allow user behavior and contributions to automatically improve the product, fueling continuous value creation.

Incentive Alignments

Where multiple user groups exist, incentives should be carefully structured so that each group gains from the presence and activity of the others.

- Marketplace participants have different incentives (buyers want variety and competitive pricing, sellers want a large customer base).

- Social network users resonate with personalization (relevant content, engaging connections) that grows with scale.

- In some setups, loyalty rewards or tiered benefits for dedicated users can encourage deeper engagement and referrals.

How Network Effects Help Founders

Competitive Advantage and Moats

One of the primary reasons founders love network effects is that they create “moats,” or defenses against competitors. When a product becomes increasingly valuable with more users, it becomes difficult for a rival to replicate that value from scratch.

- Entrenched User Base: Participants have strong motivations to stay on a platform with the most active users.

- High Switching Costs: Users lose access to established connections, content, or reputation metrics if they move to a new platform.

- Continuous Feedback Loop: Even small improvements amplify for a large network, perpetuating a leadership position.

Lower Customer Acquisition Cost Over Time

As networks grow, they often become self-reinforcing. Users attract more users, leading to organic growth and lowered marketing spend.

- Referrals and social proof encourage adoption with minimal external advertising.

- A strong brand built around an active community reduces friction in user acquisition.

- Loyal and satisfied groups of users can become brand ambassadors.

Access to Valuable Data

When platforms expand, the volume of analytics and behavioral data can expand exponentially. This data can be leveraged to:

- Enhance user experiences with personalized feeds or recommendations.

- Optimize engagement strategies (notifications, content suggestions, segmentation).

- Generate insights to drive product innovation or new revenue streams.

Challenges and Common Pitfalls

Bootstrapping the Network

Getting the first users on board is notoriously difficult. Without sufficient users, new participants see little value, which in turn makes it hard to attract more. This is often referred to as the “chicken-and-egg” problem.

- Seed with High-Value Users: Start with a small but valuable subset of users who can offer unique content or services.

- Exclusive Access, Invites, or Partnerships: Provide incentives or status for early adopters.

- Niche Market Focus: Develop strong use-cases in a narrower domain before expanding to broader audiences.

Oversaturation and Noise

While growth is desirable, overcrowding can lead to decreased perception of the platform’s quality. This can be seen in social networks cluttered with ads or irrelevant posts.

- Content Moderation: Curation ensures quality and value remain high.

- Balancing Monetization: Introducing monetization strategies that do not damage the user experience or trust.

- Fine-Tuning Recommendation Algorithms: Continually adapt so users receive relevant info amidst expanding content.

Managing Complexity

Large networks can become fragmented or overly complex, sometimes leading to a loss of the initial value proposition. Keeping the core essence of the product is essential while scaling.

- Continuous Product Research: Understand evolving user groups and tailor features to remain relevant.

- Clear Platform Policies: Provide transparent rules to maintain trust among different stakeholders.

- Scalable Infrastructure: Prevent downtime or latency issues that can erode user trust.

Strategies to Harness Network Effects

Focusing on Critical Mass

A key strategy to achieving strong network effects is to reach a “critical mass” of users who keep amplifying the value of the platform.

- Refine and optimize referral strategies early on; reward top referrers in a meaningful way.

- Utilize targeted marketing to gather user clusters that have high interaction potential.

- Structure your product so that even small circles of users can gain significant value, incentivizing them to build local sub-networks.

Cross-Side Network Effects in Marketplaces

In two-sided platforms, founders should carefully orchestrate the growth of both supply and demand.

- Balance Seller and Buyer Interests: Consider buyer acquisition tactics alongside seller incentives for listing products or services.

- Maintain Platform Trust and Safety: Implement transparent rating and review systems, dispute mechanisms, and product authenticity checks.

- Dynamic Pricing or Commission Structures: Design fee structures that scale with usage so participants remain motivated.

Viral Loops and Growth Hacking

With digital platforms, founders often experiment with viral loops to accelerate user acquisition:

- Encourage users to share or invite through built-in product prompts.

- Leverage social media integration, making it easy for users to post their activities or achievements.

- Implement referral bonuses (e.g., credit, discount codes) that reward both the referrer and the new user.

Continuous User Engagement

Sustaining the network effect requires ongoing engagement. If users leave, the network’s value diminishes.

- Gamification Techniques: Achievements, rankings, or challenges to keep people involved.

- Content Freshness: Regular content updates, user-generated material, or curated features that spur activity.

- Personalized Notifications: Subtle and relevant alerts encouraging users to log in or resume participation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Question: How do I overcome the initial hurdle of a network with few users, so it’s actually valuable to newcomers?

Answer: The key is to create a compelling experience that can function for a small number of users, even if the network is not large. Many successful founders do this by focusing on niche segments or “atomic networks”—small, dense communities that find value in a specific use case. Over time, these clusters expand, linking up to create a broader ecosystem.

Question: What if my product doesn’t typically benefit from direct interactions between users?

Answer: In that scenario, consider indirect or data-based network effects. Even if users don’t communicate directly, the product could benefit from aggregated insights that improve the overall experience for everyone (recommendations, personalization, or pooled resources).

Question: How can I keep my network high-quality when it scales rapidly?

Answer: Quality control mechanisms, moderation, and curation all become critical. Implement filters, rating systems, and robust community guidelines. Invest in user support early, especially if you anticipate fast growth; this will keep core users satisfied, reducing churn and bad experiences.

Question: What drives user loyalty on network-based platforms?

Answer: Loyalty often stems from strong community ties, personalization, and active participation. Building routines around your platform—like daily check-ins, personalized recommendations, or close-knit group chats—helps. This locks in users who value their existing network, reputation scores, or curated content libraries.

Question: How do I ensure that my network evolves rather than stagnates?

Answer: Continual innovation is essential. Observe user behavior, experiment with new features, and pivot or expand carefully as user needs change. Foster a culture of community co-creation, encouraging participants to shape the future of the platform. If the product remains static while the market changes, it risks losing relevance.

Conclusion

Network effects are a formidable force in the startup world. They can propel companies from obscurity to market leadership rapidly, provided founders understand the underlying mechanics of node connections, value flows, and critical mass. By leveraging technology wisely, designing incentives thoughtfully, and relentlessly focusing on quality user engagement, founders can cultivate robust defensibilities and exponential growth paths. As the digital landscape continues to evolve, those companies that successfully harness network effects will often define and command entire market categories. The insights and strategies discussed here serve as a foundation for navigating and capitalizing on these powerful phenomena.

Mapping Out The 16 Network Effects

Introduction: The Nuances of Network Effects

Network effects are not a binary concept; they are diverse. There are various types of network effects, and not all are created equal. Sixteen distinct types have been identified, each with unique characteristics and varying strengths.

This map serves to categorize the different network effects by strength and type, and understand their unique characteristics. The following details the 16 network effects.

1. Physical (Direct) Network Effects

Definition: The strongest form of direct network effects, where the network's value is tied to physical infrastructure.

The earliest documented commercial application was in 1907 with AT&T, which deployed physical telephones and copper wires.

AT&T's chairman recognized the power of this physical network, noting its indispensability

and monopolistic potential. The physical infrastructure presented a high barrier to entry

for competitors.

Example: AT&T's physical phone lines. Each additional

phone line increased the network's reach, making it more valuable to all users.

2. Protocol (Direct) Network Effects

Definition: Network effects arising from the widespread adoption of a standardized protocol.

Examples include:

- Fax machines: The more fax machines in use, the more people can send and receive faxes, increasing the utility of each machine.

- Ethernet: Standardized connection protocols allow devices from different manufacturers to communicate, fostering widespread adoption and network growth.

- Bitcoin: As more people adopt and use Bitcoin, its liquidity and acceptance increase, making it more valuable as a digital currency.

3. Personal Utility (Direct) Network Effects

Definition: Networks that provide direct utility to users through personal connections.

Examples include:

- WhatsApp: Users benefit from connecting with a larger number of their contacts, facilitating communication.

- Facebook Messenger: The value of the service increases as more of a user's friends and family are on the platform.

- WeChat: Combining messaging, social media, and payments increases its utility as more people use its diverse functionalities.

4. Personal (Direct) Network Effects

Definition: Social networks where value increases with the number of personal connections.

Examples include:

- Facebook: Users find the platform more valuable as their network of friends, family, and acquaintances grows, providing more content and interaction.

5. Market Network (Direct) Network Effects

Definition: N-sided marketplaces that facilitate collaboration among industry-specific nodes.

Examples include:

- Platforms connecting vendors and participants for events like weddings: More vendors and participants increase the likelihood of successful matches and collaborations, enhancing the platform's value.

6. 2-Sided Marketplace (Indirect) Network Effects

Definition: Marketplaces that connect supply and demand, creating indirect network effects.

Examples include:

- Craigslist: More buyers attract more sellers, and vice versa, increasing the volume and variety of listings.

- Monster.com: More job seekers attract more employers, and vice versa, increasing the likelihood of successful matches.

- Uber: More riders attract more drivers, and vice versa, reducing wait times and increasing service availability.

7. Platform (Indirect) Network Effects

Definition: Platforms that allow other businesses to build on them, creating an ecosystem.

Examples include:

- Microsoft OS: A larger user base attracts more software developers, increasing the availability of applications.

- iOS: A larger user base attracts more app developers, increasing the variety and quality of apps.

- Salesforce: A larger customer base attracts more developers to create custom applications and integrations, enhancing the platform's functionality.

8. Asymptotic Marketplace (Indirect) Network Effects

Definition: Marketplaces that experience diminishing returns as they grow.

Examples include:

- Uber and Lyft: While initial growth significantly improves service availability, additional users beyond a certain point provide marginal benefits, as the market becomes saturated.

9. Expertise (Indirect) Network Effects

Definition: Tools or platforms that users master and continue to use.

Examples include:

- QuickBooks: Users develop expertise in the software, making them less likely to switch, and a community of experts grows, providing support.

- Figma: Users become proficient in the design software, fostering collaboration and a shared understanding within design teams.

10. Data Network Effects

Definition: Products that become more valuable with increased data.

Examples include:

- Waze: Real-time traffic data from users improves navigation accuracy and efficiency for all users.

11. Language (Social) Network Effects

Definition: Using a common phrase or verb associated with a product.

Examples include:

- "Google it": The widespread use of "Google it" reinforces Google's dominance as the primary search engine.

12. Belief (Social) Network Effects

Definition: When a critical mass believes in something.

Examples include:

- Bitcoin: Its value and stability depend on widespread belief in its potential as a decentralized currency.

- Religions: Shared beliefs and practices unite communities and reinforce the religion's influence.

13. Tribal (Social) Network Effects

Definition: Emotional connection to a brand.

Examples include:

- Sports teams: Fans feel a strong emotional connection, leading to loyalty and increased engagement with the team and its merchandise.

14. Bandwagon (Social) Network Effects

Definition: Using a product because of its popularity.

Examples include:

- Apple products: Perceived status and social acceptance drive adoption.

- Slack: Common use in professional environments drives adoption for team communication.

15. Hub and Spoke (Social) Network Effects

Definition: Centralized network with a select few as the hub.

Examples include academic journals, TV, and TikTok.

The hub receives attention, and others consume their content.

Individuals strive to become the hub.

TikTok exemplifies this, with users aiming for algorithm recognition.

TikTok users create content hoping to be featured, gaining widespread attention and followers.

16. Reinforcement (Bonus Section)

Network effects can be reinforced.

Startups build a product, software, and network, establishing a minimum viable cluster.

Once a network effect is established, others can be added.

The process involves selecting and integrating new network effects.

Case studies demonstrate successful reinforcement.

A platform like Facebook initially builds a personal network effect, then reinforces it by adding a platform network effect (app developers), and data network effects (targeted ads).

General Mechanics of Network Effects

Network effects involve connection and interdependence. Value increases with each participant.

- Direct Network Effects: Value increases with user count.

- Indirect Network Effects: Value increases through complementary goods or services.

Benefits of Network Effects

- Increased Value for Users: Value grows with the network.

- Strong Competitive Advantage: Potential for "winner-take-all" scenarios.

- Rapid Growth: Exponential growth potential.

- Lock-in Effect: High switching costs create loyalty.

The 4 Pillars Of Defensibility

Introduction to Defensibility

Defensibility is a cornerstone of business longevity, representing a company's capacity to withstand competitive pressures and maintain its market share. In the digital era, building robust defensibility early on is crucial for category leadership. Four primary pillars define defensibility: network effects, brand, embedding, and scale.

1. Network Effects

Network effects arise when a product or service becomes more valuable with each additional user, creating a self-reinforcing loop. This mechanism establishes a formidable barrier to entry, enabling companies to dominate markets and achieve high valuations. For founders, integrating network effects from inception is vital.

Example: Airbnb, where each new host and guest increases the platform's variety and appeal, attracting more users. Tip: Design products that naturally foster user interaction and growth, encouraging viral adoption.

The success of marketplaces often hinges on accumulating both supply and demand. For instance, travel marketplaces thrive by aggregating a wide range of suppliers (flights, hotels) to attract a large customer base. Similarly, real estate platforms benefit from amassing property listings to draw in prospective buyers. This highlights the importance of supply-side aggregation in marketplace dynamics.

2. Brand

A strong brand signifies a clear consumer understanding of a company's identity and value, creating psychological switching costs. This reduces customer acquisition costs through organic growth and word-of-mouth. Brand building is particularly relevant in saturated markets or for high-value purchases.

Example: Nike, which has cultivated a brand synonymous with athletic excellence and innovation.

Tip: Consistent messaging and exceptional customer experiences are essential for building a lasting brand reputation.

3. Embedding

Embedding involves integrating a product or service deeply into a customer's operations, increasing switching costs due to disruption. This strategy is potent when combined with network effects, enhancing defensibility. It's prevalent in enterprise software, cloud services, and APIs.

Example: Slack, which becomes integral to team communication workflows.

Tip: Develop products that are indispensable to daily operations, fostering long-term customer relationships.

4. Scale

Scale defensibility is achieved by reducing unit costs as an organization grows, leading to economies of scale. This can create a flywheel effect, driving further cost reductions and growth. While powerful, scale effects are more applicable to mature companies, particularly in manufacturing and infrastructure-heavy sectors.

Example: Walmart, which leverages its vast distribution network to achieve cost efficiencies.

Tip: Focus on scalability from the outset, but prioritize other forms of defensibility in the early stages.

Furthermore, companies can leverage scale by investing heavily in proprietary content, reinforcing defensibility through content ownership. This strategy demonstrates how scale can be used to solidify a company's market position.

Intellectual Property (IP)

In sectors like science and biotechnology, IP is a crucial defensibility pillar. Unique scientific innovations with proprietary IP can form the core of a company's competitive advantage.

Example: Pharmaceutical companies with patented drug formulations.

Tip: Secure strong IP protection for unique technological or scientific innovations.

Navigating Defensibility as an Early-Stage Founder

Defensibility pillars are not mutually exclusive; successful companies often combine them. Early-stage startups should prioritize network effects for their digital nature, scalability, and capital efficiency. Over time, other pillars like brand, embedding, and scale can be incorporated.

Tip: Begin with network effects and gradually layer in other forms of defensibility as your company evolves.

Understanding the different types of network effects is essential. There are 16 distinct types, and founders should consider how they can reinforce their network effects over time, adding layers of defensibility. This strategic approach to building and reinforcing network effects is crucial for creating defensible and successful businesses.

Network Bonding Theory

Introduction

Network Bonding Theory explores the fundamental mechanisms behind network formation. With the advent of Web3, the intricate processes of network construction have become more transparent. This increased visibility enables a deeper understanding and application of these mechanisms in startup development, allowing for the strategic building of robust and resilient networks.

The Shift from Implicit to Explicit Compensation

Historically, companies have often made implicit decisions regarding the compensation of network participants, or nodes, primarily through equity and salary structures. By transitioning to explicit calculations, companies can more accurately assess and manage the value contribution of each node. This shift allows for a more data-driven approach to compensation, ensuring that rewards are commensurate with the value each node brings to the network.

Single Player vs. Multiplayer Mindset

Adopting a multiplayer mindset is essential for building thriving networks. This involves a strategic approach to integrating and compensating diverse nodes within the network, effectively transforming the company into a dynamic multiplayer ecosystem. This perspective fosters collaboration and incentivizes participation, driving network growth and engagement.

Your Startup As a Network

A startup can be conceptualized as a network comprising various nodes, including employees, customers, press, and investors. Each node is motivated to join and contribute to the network, often through incentives such as equity offerings that typically decline geometrically over time. This model underscores the importance of strategic node acquisition and retention.

Explicit Calculation of Node Value

Utilizing tools and spreadsheets to quantify the value impact of each node enables companies to determine appropriate compensation and develop effective negotiation strategies. This data-driven approach ensures that compensation aligns with the value contributed by each node, fostering a fair and incentivized network environment.

Factors in Node Compensation

Several factors influence node compensation, including the time elapsed since the company's inception, the potential value of the node, post-bonding engagement levels, and overall performance. These considerations allow for a nuanced approach to compensation, ensuring that it reflects both the node's potential and their actual contributions to the network.

Types of Compensation

Compensation can take various forms, including product value, cash, equity, discounts, status, access to exclusive opportunities, decision-making power, software features, community membership, real-world perks, mission alignment, relationship commitment, fungible tokens, and NFTs. This diverse range of compensation options allows companies to tailor incentives to meet the specific needs and motivations of different nodes.

Unequal Nodes and Token Compensation

Recognizing that nodes are not created equal is crucial for effective network management. Fungible tokens can be employed to align incentives, as demonstrated by Paris Saint-Germain's compensation of Lionel Messi with fan tokens. This approach allows for the strategic distribution of value within the network, ensuring that high-value nodes are appropriately incentivized.

The Future of Node Compensation

The landscape of node compensation is evolving with the emergence of tokens and NFTs. Founders must adapt to these new forms of value exchange to remain competitive. This includes understanding the implications of these technologies for network governance and incentive structures.

Beyond Monetary Incentives

While financial incentives are important, human factors such as relationships and personal preferences play a significant role in node recruitment. Recognizing and leveraging these factors can enhance a company's ability to attract and retain valuable network participants.

Network on Network Wars

The future will witness increased competition between networks. Understanding node value, take rates, network pollution, status, and node fungibility is essential for both attacking and defending networks. This includes developing strategies to attract and retain high-value nodes while minimizing the impact of competitive threats.

Real-World Examples

Examples such as SiriusXM's recruitment of Howard Stern and SushiSwap's vampire attack on Uniswap illustrate the principles of network competition. These cases highlight the importance of strategic node acquisition and the potential impact of competitive attacks on network stability.

Final Thoughts on Network Bonding Theory

Understanding and measuring network nodes, compensating them effectively, and adapting to network competition are essential for building and maintaining successful networks. This requires a strategic approach to network management, focusing on data-driven decision-making and continuous adaptation to the evolving network landscape.